I was excited about todays lecture as in Richard’s powerpoint title it contained the word ‘time’. I have always wanted to learn and find out more about time and timezones including the international date line.

Horology is the study of time and as humans we base our whole lives around this concept of ‘time’. Our life is a trickling hourglass, and when times up that’s our time up on this earth. We constantly are looking at clocks, updating calendars and setting countless alarms because as humans, many of us are useless as time keeping. It is the core to our daily schedules, without it we would be lost.

Horology is the study of time and as humans we base our whole lives around this concept of ‘time’. Our life is a trickling hourglass, and when times up that’s our time up on this earth. We constantly are looking at clocks, updating calendars and setting countless alarms because as humans, many of us are useless as time keeping. It is the core to our daily schedules, without it we would be lost.

Throughout our childhood up to adolescence we become professionals at timing our every move. But this only comes from faults and mistakes. We’ve only not too rarely misjudged how long it will take to get up in the morning, ready to leave the house for school or work. You set your alarm the night before (3 or 4 alarms in my case) thinking in your head it will take you approximately x minutes to do each on your tasks in the morning, and by setting my alarm at 8:00am i should make it out the door at 8:45am to make it to school for 9:00am. BLEEEEP BLEEEP BLEEEP *snooze* … BLEEP BLEEP BLE. It’s 8:09am, you’ve slept in. (9 minutes off our time surly won’t make much of a difference). You’ve showered, gotten dressed, styled your hair and put some make-up on, eaten breakfast, packed your bag ready to go and your watch reads 8:51am. We know from experience that it takes 15 minutes to get to the school gates but you’ve only left yourself 9 minutes. You’re going to be late. You’ll know better for next time (hopefully). Now that I am 19 years old I am an expert at time keeping. I deliberately set my 3/4 alarms earlier than the time I need to get up at so I can even fit in a bit of 5 minute snooze time. I’ve dropped the hair na make-up and I know i can get ready in 30 minutes leaving the last 5 minutes for brushing my teeth and getting out the door perfectly on time.

This scenario is all too familiar with the majority of the nation and has a lot to do with fundamental mathematics. During the module we have spoken about Liping Ma. They categorised mathematics into 4 categories, these are: connectedness, multiple perspectives, basic ideas and longitudinal coherence (Ma, 2010). Within these 4 categories are what skills are needed for time management. You need to be good at the skills of organisation, estimation, planning, problem solving, sequencing events, etc.

Safe to say without our digital/analogical friend we would find it hard to tell the time of day or what day it is. Which brings me onto how we ever figured out time in the first place. Why did we need time? Did we always know it was time for dinner or time to get up out of bed? And what aided us to get to our 24 hour days? Richard asked us why was time important to humans in the first place? I answered that humans need to figure out time for farming seasons in order to survive. This lead onto, do other animals need to know time? We came up with the answer yes, they might not have busy schedules like us humans, but they are clever and migrate in the winter to somewhere warmer. So indeed they must have figured out that the cold weather relates to a certain time of year.

Before mechanical clocks were invented, we used inventions such as sundials and obelisks to help us tell the time. They tracked the movement of the sun through out the days so we could figure out that noon was when the sun is at its highest point in the sky and also figure out seasons, how long the sun waved over the sky in the day told us if it was summer (longer sky time) or winter (shorter sky time). The sun shines on the sundial and casts a shadow onto the face of the dial, alining with different hour-lines (sundial, 2017). Another interesting way that we think we used to attempt to first tell the time was with a manmade structure in Ireland called Bru na Boinne (or Newgrange). The building has a long, hollow passage way running all the way through the building end to end. Once a year during the winter solstice (the shortest day of the year) at 9:00am the sun shines right the way through the passage way with a bright beam for only a few minutes. Being able to understand the time and season was critical for survival, they need to know when to plant and harvest crops so when the sun shone through the building they would be able to understand its winter (Turtle, 2016).

In a day we have 24 hours on Earth. This isn’t the same on all planets. On Mercury, the year is shorter than it’s day…WHAT? This is because Mercury is closer to the sun so therefore it orbits the sun faster than we do on Earth. So because of this the planet Mercury turns slower than the time it takes to go around the sun once. So technically if you lived on Mercury you’d have a birthday EVERY SINGLE DAY!!! But why 12/24 hour time on Earth? One theory is that it is based on ancient Egyptian time. They said there was 10 hours of day, 10 hours of night, 2 hours of half-light day (dawn) and 2 hours of half-light night (dusk). They arranged these into 10 day groups, these were called decans and based on zodiac signs made of stars in the sky. The Egyptians must have understood the mathematical principle of ordinal sequencing, relative equidistance and that the Earth was spinning continuously, which they figured out from the stars.

Do you ever come across the situation where you’ve set your alarm for say 9:00am and you wake up at 8:59am. Spooky right!? Some may say that you therefore have an amazingly accurate body clock. Your body has an internal body clock which tells it what to do and when to change its behavioural, mental and physical states at certain times of the day. The are called Circadian Rhythms. The respond to the lightness and darkness of a living things environment, therefore being asleep and awake effects these rhythms. And it’s not just humans that respond to circadian rhythms, animals, plants, fungi and microbes do too!

Do you ever come across the situation where you’ve set your alarm for say 9:00am and you wake up at 8:59am. Spooky right!? Some may say that you therefore have an amazingly accurate body clock. Your body has an internal body clock which tells it what to do and when to change its behavioural, mental and physical states at certain times of the day. The are called Circadian Rhythms. The respond to the lightness and darkness of a living things environment, therefore being asleep and awake effects these rhythms. And it’s not just humans that respond to circadian rhythms, animals, plants, fungi and microbes do too!

Research shows that in the artic, the lack of daylight effects the inhabitant animal’s circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are only seen in the parts of the year that have daily sunrises and sunsets. One species of reindeer only has circadian rhythms in spring, autumn and winter but not in summer. Butterflies also have in interesting circadian rhythm which lies in their antenna! This clock in their antenna knows when to migrate during the autumn into winter. In plants their circadian clocks tell them when it is the right season for their flowers to bloom for the best chance of pollination (Circadian rhythm, 2017).

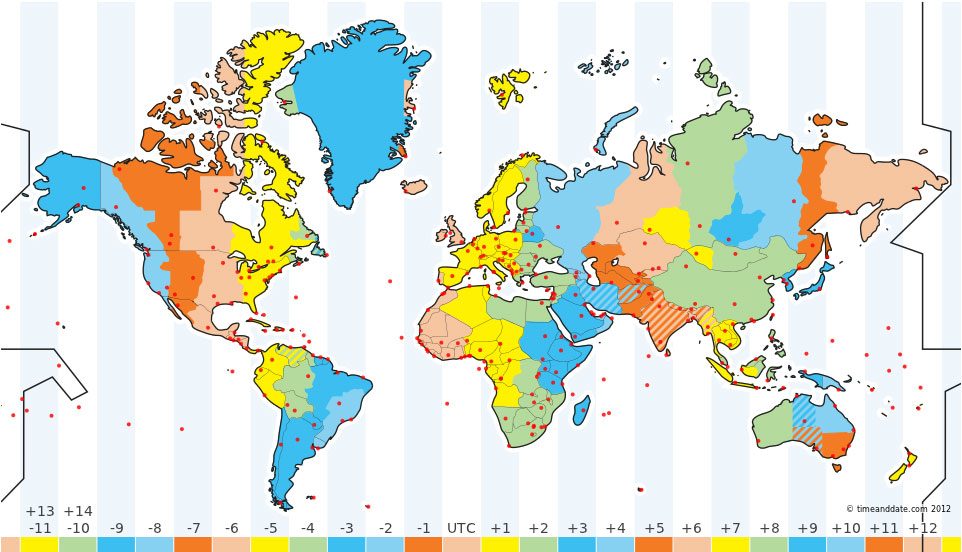

Your circadian rhythms can be disrupted in many ways. Once way is due to jet leg. When you have flying and you pass through the separate time zones, your body clock will be different from the local time zone clock. For example, if you fly east from Perth to Sydney in Australia, you “gain” 3 hours. When you land and wake up to it being 6:00am in Sydney, your biological clock is still running with the Perth local time, so your body is confused and thinks its the middle of the night at 3:00am. After a few days you body clocks with reset but this can make you more tired as your sleeping patterns are effected (Circadian rhythms, 2017).

In 1880 GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) was introduced as the central point for time zones across the world. Time zones split up the world, longitudinal ways, so that most countries fall into one time zone. This meant that each zone to the right of GMT increased by an hour and each zone to the left of GMT decreased by an hour until they meet around the other side of the Earth at the IDL (International Date Line). It is set up this way as each part of the world gets sunlight and night time at different times of the day as the Earth is spinning. Some argued that the world should have “practical time”. This means it would be the same time around the world, for example in the Uk we would be having our breakfast at 7:00am at sun rise and people in eastern Australia would be having their breakfast at 6:00pm at sun set. Seems a bit silly to me as then the Australians would be arriving at work in the dark…

During the year, in many countries, we have a concept called ‘daylight saving’. This is when we lose and gain an hour each year to help our society to continue to function and produce food when the day light decreases. In the spring time we gain an hour, we “spring” forward, and in autumn we lose an hour, we “fall” backwards. This mean in winter we will have lighter mornings as in winter the day light get shorter until the 21st of December (shortest day of the year).

Once you reach the other side of the world from the UK you will reach the International Date Line, about 180 degrees west or east of GMT. This is where time is either one day ahead or one day behind. The imaginary line from the north pole to the south pole is not straight though. It zigzags down the Earth’s surface to avoid political and country borders so that it doesn’t split any countries into two as that would be very confusing if your neighbour was in Tuesday and you were in Monday. When you cross the IDL from west to east (Australia to America) you take away a day, and if you cross east to west you add on a day. This is basically TIME TRAVEL, am I right!? Once a day for 1 hour and 59 minutes there are 3 dates present at the one time. Between 10:00 and 11:59 the 3 countries; American Samoa, New York and Kiritimati all have different dates. For example April 1st, April 2nd and April 3rd (What Is The International Date Line (IDL)?, 1995). So you can set off from New Zealand and arrive in Hawaii the day before you set off!

Overall, this is my favourite example of Liping Ma’s theory of connectedness (2010). Time is all about Mathematics and I feel Richard gave us a good insight into how they link and are used in our everyday lives. I have developed the understanding of connectedness throughout this topic and plan to deepen my understanding of this for my future students when connecting time in maths to wider contexts.

References:

Ma, Liping. (2010). Knowing and Teaching elementary mathematics: teachers’ understanding of fundamental mathematics in China and the United States. New York: Routledge.

Sundial. (2017). [Website]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sundial. (Accessed 06/11/17).

Turtle, M. (2016). [Website]. Available at: https://www.timetravelturtle.com/visit-newgrange-dublin-ireland/. (Accessed 07/11/17).

Circadian rhythm. (2017). [Website]. available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circadian_rhythm. (Accessed 07/11/17).

Circadian rhythms. (2017). [Website]. Available at: https://www.nigms.nih.gov/education/pages/Factsheet_CircadianRhythms.aspx. (Accessed 07/11/17).

What Is The International Date Line (IDL)? (1995).[Website]. Available at: https://www.timeanddate.com/time/dateline.html. (Accessed 07/11/17).