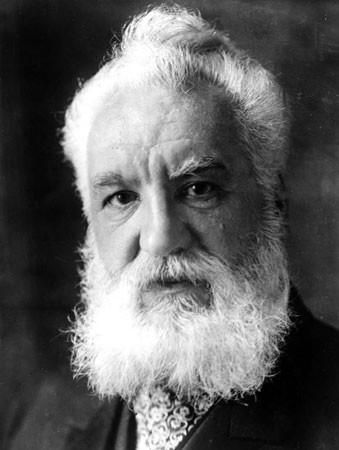

Phones are an integral part of daily life. But people still get excited at the announcement of the latest mobile phone. It was no different back in the late 19th century, when the notion of communicating to someone else miles away by means of a machine was something quite new. Crowds gathered to see demonstrations of this technology. Even Queen Victoria was delighted by it. And the man who pioneered it was Alexander Graham Bell.

Phones are an integral part of daily life. But people still get excited at the announcement of the latest mobile phone. It was no different back in the late 19th century, when the notion of communicating to someone else miles away by means of a machine was something quite new. Crowds gathered to see demonstrations of this technology. Even Queen Victoria was delighted by it. And the man who pioneered it was Alexander Graham Bell.

Bell had a particular interest in the spoken word. His father and his grandfather were teachers of elocution and his father a pioneer in the teaching of speech to the deaf, a hitherto largely neglected area.

Bell was born in South Charlotte Street in Edinburgh on 3 March, 1847. He was educated at the Royal High School but left early to become involved in his father’s work and to spend time with his grandfather, the Professor of Elocution at the University of London. Young Bell was fascinated by devices and built a model ‘speaking machine’ which he based upon a sheep’s larynx.

An instrument called a ‘telephone’ already existed at this time. It had been invented by Philip Reis, who was also working in Edinburgh. It was a primitive piece of apparatus that transmitted sounds across space using electric wires and a battery. Bell would probably have heard of the ‘telephone’ but there had been no realisation of its potential. For a time, Bell taught ‘Visible Speech’ to deaf girls in Elgin. He used a system devised by his father that used symbols to represent groups of sounds. He also lectured in London. In 1870 the family emigrated to Canada and Bell took up the Chair of Vocal Physiology at the University of Boston, a leading centre for science and technology.

‘Watson, please come here, I want you’

Bell’s invention of the telephone arose from his continued interest in improving facilities for deaf people. He sought to devise an instrument, an artificial ear or hearing aid, and did so by linking two magnets by wire charged with a current from a battery. Vibrators at each end of the system allowed an electrical signal created by a sound to be reconverted to sound at the receiving end. It is traditionally thought that the first transmission by the prototype of the modern telephone happened by accident when Bell called to his assistant in the next room: ‘Watson, please come here, I want you’.

It is more likely that the potential of the device was realised earlier than this and there was certainly a period of development before Bell patented the invention in 1873. The following year the ability of the telephone to carry the human voice over a long distance was demonstrated at an exhibition in Philadelphia. The Bell Telephone Company was founded and advocates such as Lord Kelvin, who was responsible for the laying of the first transatlantic cable and the Emperor of Brazil, endorsed the new discovery.

Popular Acclaim

The telephone was also demonstrated to Queen Victoria who was delighted by it and by 1879 the first telephone exchange had opened in London. Although the telephone gained popular acclaim and interest quickly spread across the United States and the United Kingdom, Bell had great difficulty in proving his claim to be the inventor. In time, however, he became wealthy from it and turned his attentions back to his work with the deaf. In later life he went on to inaugurate the Volta Laboratory in Washington DC, for the ‘diffusion of knowledge for helping the deaf’. He worked with Thomas Edison on developing the phonograph. He also founded the American journal ‘Science’ and became interested in aeronautics, especially kites and gliders.

Bell became an American citizen but he returned to Scotland many times and during one visit set up a school for deaf children. From the 1880s he made his home in Nova Scotia. He died there, on Cape Breton Island, in 1922.

Images © Hulton Getty, National Museums Scotland | Licensor Scran