Many children and young people in the school will have neuro-developmental differences that influence how they function in a social world that is shaped, for the most part, by people without such differences. Knowledge and understanding of the differing needs and requirements of autistic people has only recently begun to truly influence mainstream practice. Even so, the good baseline knowledge, understanding and experience of practitioners is not always shared by the wider population. Autistic people’s experience is seldom kept in mind when, for example, school buildings, restaurants and shops are designed.

Autistic people often differ in how they communicate and interact socially when compared with non-autistic people. They may have strong interests or passions about specific activities or interests, and may enjoy routinised, repetitive experiences. Their preferred topics of conversation or their general social communication style may make it more difficult for them to establish friendships they can feel secure and calm in.

Autistic people often experience the sensory world differently, and can be either hyper or hypo-sensitive. Many autistic people will identify sensory triggers like the school bell, the canteen, and large, busy spaces, as quite triggering and difficult to cope with. This can be evident at major transitions such as entering or exiting the school building, break, lunch time, and changeovers between classes.

An inclusive, neurodiversity aware school will find that autistic children and young people are more likely to attend and engage in their learning. Whole school commitment to training in autism and neurodevelopmental differences is therefore critical, as the anxiety that this population of children and young people can experience is often routed in:

- sensory and environmental triggers

- their social communication experiences

- their relationships with peers and staff

- the inconsistencies they experience with respect to rules and expectations (even when these may appear subtle to others)

- multiple transitions

With this level of vulnerability and risk, all staff members must develop their skills in communicating with children and young people in an autism informed way. Some of the guiding principles of doing so include:

- Keeping things consistent by being predictable and routine based

- Using concrete visual cues and materials to support language and communication of ideas, expectations and plans

- Practitioners being specific and accurate in their use of language, and owning any communication errors that they make, which is highly likely given how prevalently most people use creative and idiomatic language in their daily communication

- Practitioners being aware that the content of what is said carries more weight than all other elements of verbal communication (e.g. speech prosody, volume, intonation, pitch, and non-verbal communication)

- Being aware that the issue of communication breakdown between neuro-typical and neuro-diverse individuals is one of a double empathy problem, it’s not the individual with autism that has sole ownership of the problem

- Being aware that a person with autism will often have a base level of anxiety that is much higher than most neuro-typically developing people, meaning they are more vulnerable to emotional dysregulation, emotional drain and shame if they are not coping on a regular basis

Autism can be thought of as a condition of extremes. Therefore, autistic people are much more vulnerable to the effects of school experiences that most people would find anxiety provoking to some extent, and also to some experiences that most people would find unproblematic. It stands to reason that, as a result, some will develop EBSA behaviours. Indeed in some cases, EBSA is an indicator of an underlying autistic profile that has been masked for some time by the young person, often at great emotional cost.

With such a varying profile of need and experience, autistic people need to be understood individually. Plans need to be tailored specifically in partnership with them to ensure they meet their needs and offer them the right learning experience. However, there are patterns within the autistic population that point to specific adaptations and strategies that are worth considering, many of which would also help children and young people with EBSA who are not autistic. More information on the features of effective support for those with autism can be found in Appendix H.

Where young people are experiencing acute anxiety, they are more likely to exhibit higher levels of rigidity, and this can develop into controlling behaviours. At times like this the child or young person is likely to feel that:

- The social world is extremely difficult to navigate

- Their attempts to communicate are misinterpreted by others

- Their attempts to understand the communication of others is failing

- Their system for navigating their social world is not working

- Their social world is a place where they are not safe, leading to fear, anxiety, and more stress

- They have few options to choose from, they are trapped, so the most effective action is sabotage – that way they are making a firm choice, and taking back some sense of control.

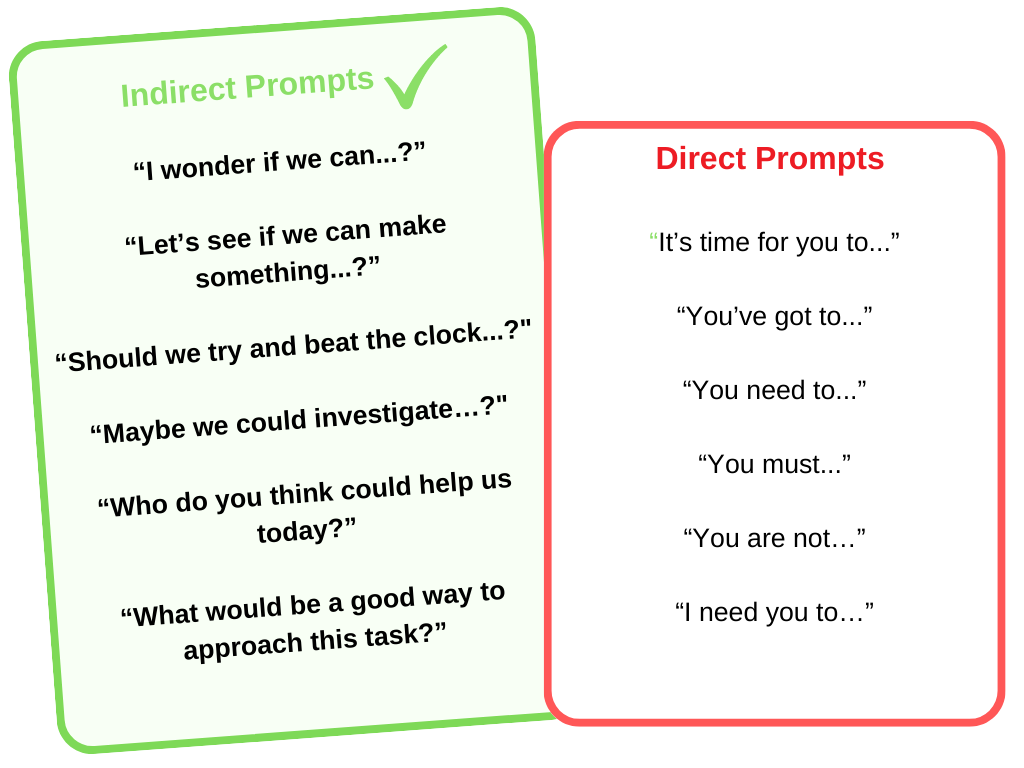

In these cases, practitioners may experience more success by using indirect prompts. These can help reduce feelings of anxiety over time, and minimise the risk of heightened emotional responses. Examples are detailed in Figure Six:

Figure Six Indirect prompts to support EBSA

These strategies are likely to help anyone with anxiety, autistic or not. For some, their level of anxiety will be at such a height that a very detailed, progressive plan will be needed to support their gradual reintegration back into the school environment.