From the title, it would be understandable for you to think I had gone mad. In fact, quite the opposite. I had a wonderful lesson today exploring the joys of number systems and place value. Although at first it was not as clear, it was exciting watching the numbers evolve and make sense in front of my very eyes.

The first thing that struck me about the lesson was looking at a counting system used by shepherds when counting their sheep in medieval times:

This system uses a base 20 system, where when the shepherd counted 20 sheep, they would  put a stone in their pocket to signify 20. They would then start again until they again reached 20 (40 total) and another stone in the pocket, and so on.

put a stone in their pocket to signify 20. They would then start again until they again reached 20 (40 total) and another stone in the pocket, and so on.

You can see a degree of repetition in this system with 11 (Yan-a-dik) literally standing for one and ten. However, what perplexes me is why they have tags for numbers 6 through 9, as in their system they do not seem to be used again. They have no need to have numbers beyond twenty, as after this they begin again, so why not make 6 “Yan-a-pimp”? This seems, to me, a flaw in their system, which otherwise seems to be a sensible system for them.

As I had previously read about this system before the lesson, seeing it come up automatically hooked me. This I can relate back to the classroom, as if children, like I did, recognise what they are being taught, they will associate with it much better, and I believe will be more likely to take the information on board. I think this links to Liping Ma’s idea of ‘interconnectedness’ (p122) (Ma 2010) as relating new learning to what the children already know is likely to engage them and make them eager to learn.

My excitement grew when we were then told that “Yan Tan Tethera” was the name of a Scottish Country Dance and the crib (instructions) was put on the screen, almost like a foreign language to everyone else, but looked so familiar to me. It gave me a sense of homely warmth, that I can only imagine children feel when they recognise what is on the screen in front of them. This again links back to the idea that children are more likely to be engaged in the learning if they can relate to it. For example, talking about farming to children in the inner city will not resonate with them. I am hoping to try this dance out in my dancing group and will update my blog with it soon.

My excitement grew when we were then told that “Yan Tan Tethera” was the name of a Scottish Country Dance and the crib (instructions) was put on the screen, almost like a foreign language to everyone else, but looked so familiar to me. It gave me a sense of homely warmth, that I can only imagine children feel when they recognise what is on the screen in front of them. This again links back to the idea that children are more likely to be engaged in the learning if they can relate to it. For example, talking about farming to children in the inner city will not resonate with them. I am hoping to try this dance out in my dancing group and will update my blog with it soon.

To us using base 10, or decimal, the idea of any other base system seems alien to us. The most  common base system to us, apart from base 10, is binary. Binary is a base 2 system used by computers consisting of only two digits – either a 0 or a 1. Having done Standard Grade Computing, I am fairly familiar with how binary works and how you can make any number using this system. The way I know how to use binary is using a place value system, doubling the numbers each time. This is because in base 10 system you have place values of ones, tens, hundreds etc, where the columns are 10x as much. Because it is only a base two system, the numbers only double each time. There are some examples of binary below:

common base system to us, apart from base 10, is binary. Binary is a base 2 system used by computers consisting of only two digits – either a 0 or a 1. Having done Standard Grade Computing, I am fairly familiar with how binary works and how you can make any number using this system. The way I know how to use binary is using a place value system, doubling the numbers each time. This is because in base 10 system you have place values of ones, tens, hundreds etc, where the columns are 10x as much. Because it is only a base two system, the numbers only double each time. There are some examples of binary below:

32+16+4+2+1 = 55

64+4+1 = 69

By adding up all of the numbers with a one in that column, you can work out what number the binary represents.

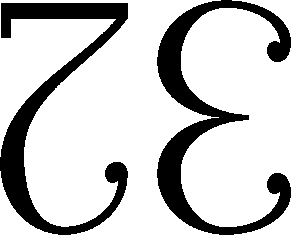

With this idea in mind, it makes looking at other base systems much easier. For example, we then looked at base 12 systems, which is thought by many to be a more appropriate base system than base 10. Base 12 includes 2 extra single digits to replace what we know as ten and eleven (respectively shown in the picture left). These extra numerals are needed as the numeral “10” uses two columns. In the base 12 system there is a “12” column rather than a “10” column. The video below explains this very well, however, instead of these digits above, she is using T and E to represent ten and eleven.

As you can see above, decimal columns are multiplied by 10 each time, and binary numbers are multiplied by 2. This then translates to dozenal numbers being multiplied by 12 each time, as you can see here.

There are some who have suggested that a base 12 system would make more sense, especially in terms of looking at fractions like 1/3 and 1/4, which are not as neat in decimal. This moves on to the fact that 12 is divisible by more numbers than 10 (1,2,3,4,6,12 rather than 1,2,5,10). 12 is a fairly common number in terms of maths, looking at time especially.

Note: these clocks are commercially available.

In conclusion, this is a confusing topic to get your head around, which is exactly what some children may feel when faced with what is difficult to them. It is important that we give children the chance to play with and explore the numbers, as we were given the chance to do, which really helped me understand the topic. Children should, in my opinion, be supported, but should be encouraged to be explorers in order for them to feel the sheer joy of what maths truly is.

References

Ma, L. (2010) Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics. (Anniversary edn). Routledge. Oxon.