What practical measures turn these principles into reality?

Below are some suggestions:

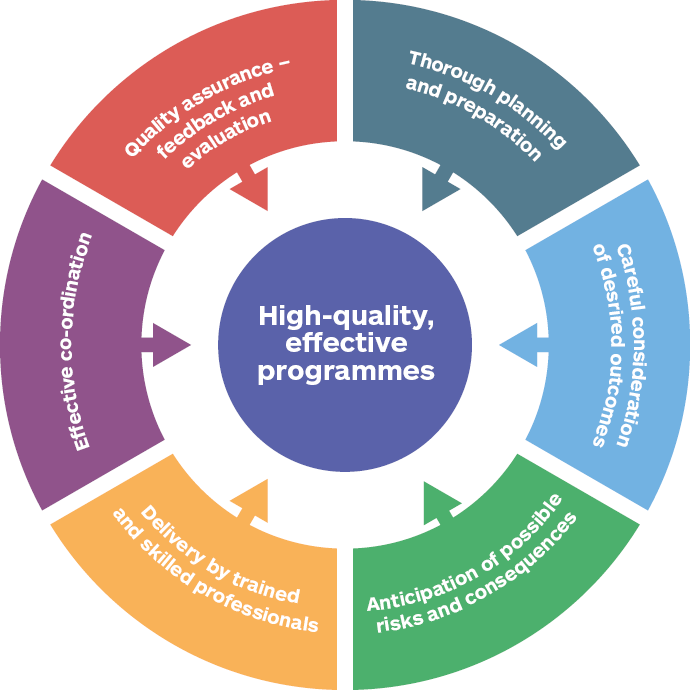

Thorough planning and preparation

This is the most important step for creating effective programmes.

Taking time to think about your programme and about your partnership(s) is worth the effort and will help clarify and generate ideas.

One approach is to carry out a scoping exercise. Essentially, this is an intellectual investigation into all aspects of the programme.

The scoping exercise

First, produce rough notes. These might include:

- Your own thoughts

- Initial, un-worked-out ideas

- Suggestions from others

- Inspirational quotes

- Key words/statements (‘buzz’ words)

- Information from policy/strategy documents

- Insights from developing and implementing your own programmes

- Observations from other examples of education programmes.

The content might include notes about:

- Strategic vision/objective

- References to policy documents

- Specific aims/intentions

- Values underpinning partnership working

- Outline of a partnership agreement1

- Types of learning events/challenges

- Desired outcomes/achievements/benefits

- Possible risks/consequences

- Details of personnel

- Anticipated training needs

- Work-relevant contexts/tasks

- Contacts/networks

- Programme legacy

- Organisational structures/locations

- Operational procedures/processes

- Funding opportunities/sources

- A cost analysis

- Resources required

- Target audiences

- Organisational factors (e.g. health & safety; insurance; school/parental permissions; logistics).

Review and revise your notes until they are as complete as possible. Retain them for future reference – they will provide a prompt and a reminder of your original thinking.

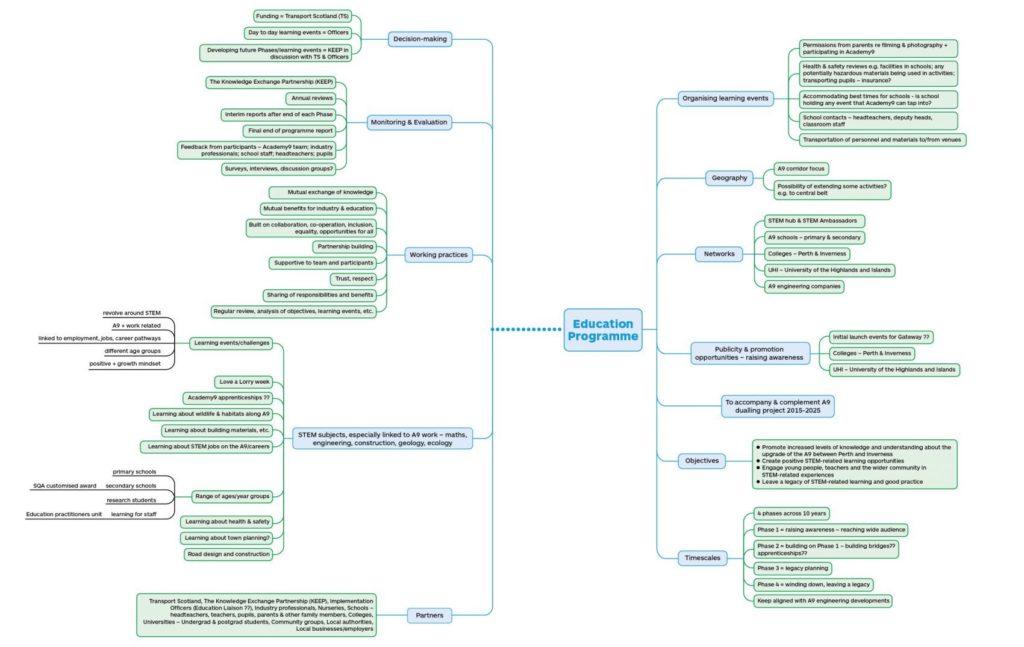

Then organise the notes more formally into a plan, using headings, sub-headings, visual diagrams, etc. On the following pages is a partially completed example (from Academy9) in the form of a mind map.

Example of a scoping exercise

Developing an educational framework2

As part of the planning process, you might consider developing an educational framework.

This is a structured outline of your programme showing timelines, phases/stages, core learning events and challenges and legacy planning.

The framework need not be very detailed, but it will reflect your current thinking and plans; regard it as a working document to be reviewed and updated as appropriate during the lifetime of the programme.

Planning is a continuous process. It doesn’t cease when implementation begins.

Further planning will be needed when the learning events and challenges are being organised and this is likely to generate more ideas and strategies which should feed back into your plan or educational framework.

This continuous approach helps ensure a dynamic element to the programme, propelling things forward and generating momentum.

Careful consideration of desired outcomes

It is important to have a vision.

Having a clear understanding of anticipated aims, achievements and benefits of the programme helps shape your planning, preparation and decision-making.

Underpinning all these features is the principle of creating and sustaining high standards, expectations and quality for all participants.

Anticipation of possible risks and consequences

No planning or preparation can completely eliminate risks, obstacles or unintended consequences.

Risk assessment should be embedded in the planning and preparation at each stage of the programme.

Delivery by trained and skilled professionals

Personnel involved in delivery of the programme need to be appropriately briefed and trained.

For example, young industry professionals may be unfamiliar with the types of language and methods needed to engage young people in a classroom context and input from educational practitioners (e.g. teachers, consultants) acting as a ‘critical friend’ can help alleviate any potential issues or anxieties.

Equally, industry professionals need to share their knowledge and expertise so that learning activities (challenges) accurately reflect the realities of work.

For example, Industry Insight days could be offered to teachers/practitioners to support their familiarisation with the industry context.

This is where knowledge exchange is crucial.

In Scotland, engagement with schools and early learning centres also requires all interventions to be closely aligned with the curriculum3 experiences and outcomes4 and benchmarks for assessment5

Effective co-ordination

Overall co-ordination of the education programme can be managed (e.g.) by one individual or group.

For example, this could be a management group responsible for strategic planning and goal setting.

Measures for facilitating a two-way information flow between delivery team members and the individual/management group is essential.

Quality assurance – feedback and evaluation

To ensure high standards, there needs to be reliable quality assurance.

The programme should be monitored, feedback collated, and evaluation carried out.

Both quantitative and qualitative data should be collected, as each method provides insight into the programme’s success. Delivery staff should have frequent opportunities to reflect on and review the events and challenges to make improvements to current practice.

This instils feelings of joint ownership and engenders a co-operative outlook.

The end of each phase of the programme should prompt an evaluation.

Embedding quality assurance ensures the merit of the programme and can contribute to its dynamic and evolving nature.

Implementing the programme

Implementation assumes prior planning and preparation.

Learning events/challenges need to be designed, venues agreed and timings arranged.

You should consider what the priorities are for initial implementation.

Is the aim to reach a wide audience? To target a specific group of people? To tackle a particular task?

Thinking about these questions helps you organise.

Implementation raises practical issues about programme content, timing, venues and resources:

- How quickly can the first learning events be set up?

- Which venues are most easily and quickly accessed?

- How much time is needed to get approval?

- How quickly can funds be authorised?

- Who are the most appropriate personnel to deliver the learning events?

- Are materials for the events immediately available or do they have to created?

Some factors affecting decision-making will be beyond your control – for example, the imminent start of the school term, or an unrelated event taking place at the same venue which could provide a platform for your programme.

The initial run-through of a learning event should be treated as a pilot, with opportunities to reflect, review and, if necessary, introduce improvements.

As the programme rolls out, implementation can require new venues, different audiences, fresh challenges and materials.

Sustaining a dynamic and evolving programme

An effective education programme has to retain the commitment of all participants for its duration.

For this reason, it needs to be appropriately ambitious, involving a willingness to experiment and test boundaries.

This may seem counterintuitive to the pursuit of success but as any scientist will explain, even less successful experiences provide insights that can be used for improvement.

This approach contributes to what is termed a ‘growth mindset’6 – a belief that most things are possible with perseverance, learning and effort.

It is an approach to which young people seem very responsive and which should form part of any education programme.

It is also an approach that motivates and encourages people to engage actively, thereby enhancing their wellbeing and building resilience – the ability to ‘bounce back’ after disappointment.

Characteristics like this have been referred to positively as ‘meta-skills’ – qualities of “self-management, social/emotional intelligence and innovation skills”7.

The Career Education Standard 3-18 (CES 3-18)8 makes these characteristics explicit through its ‘I Can’ Statements, which provide educators with a checklist against which links between the curriculum and the world of work can be measured.

The document covers the five curricular stages – Early Level to Senior Phase – reinforcing the benefits for pupils of clarifying the relationships between school subjects and career pathways.

In support of progression planning, the CES 3-18 also describes the entitlement for learners and expectations on teachers, employers, Skills Development Scotland and parents.

In this context, education programmes based on work-relevant experiential learning become increasingly relevant.

References

1 – See for example, The importance of partnership planning to deliver high quality, work-related learning – Developing the Young Workforce Blog (glowscotland.org.uk)

2 – See for example,

3 – Education Scotland, What is Curriculum for Excellence?

4 – Education Scotland, Curriculum for Excellence – Experiences and Outcomes, Available at: Experiences and outcomes | Curriculum for Excellence | Policy drivers | Policy for Scottish education | Scottish education system | Education Scotland

5 – Education Scotland, Curriculum for Excellence Benchmarks

6 – Dweck, C. (2006), Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, New York: Ballantine Books.

7 – Enterprise & Skills Strategic Board, Working Collaboratively for a Better Scotland, October 2018, p. 26.

8 – Education Scotland, Skills Development Scotland & Smarter Scotland (2015), Developing the Young Workforce – Career Education Standard (3-18), Education Scotland