- Adults who know the child as a learner. “Responsive and intentional planning approaches start with our observations and interpretations of the baby or young child’s actions, emotions and words. This tells us what the child needs for us to provide in their learning environment. A child-centred approach to planning learning will help the child connect each new discovery to what they already know.” (Education Scotland, 2020, p. 63).

- Responsive planning is supported through high-quality learning environments, interactions and experiences. Nurturing environments value and promote curiosity, imagination, creativity, wellbeing and resilience.

- The 7 principles of curriculum design are considered when planning for quality spaces, experiences and interactions.

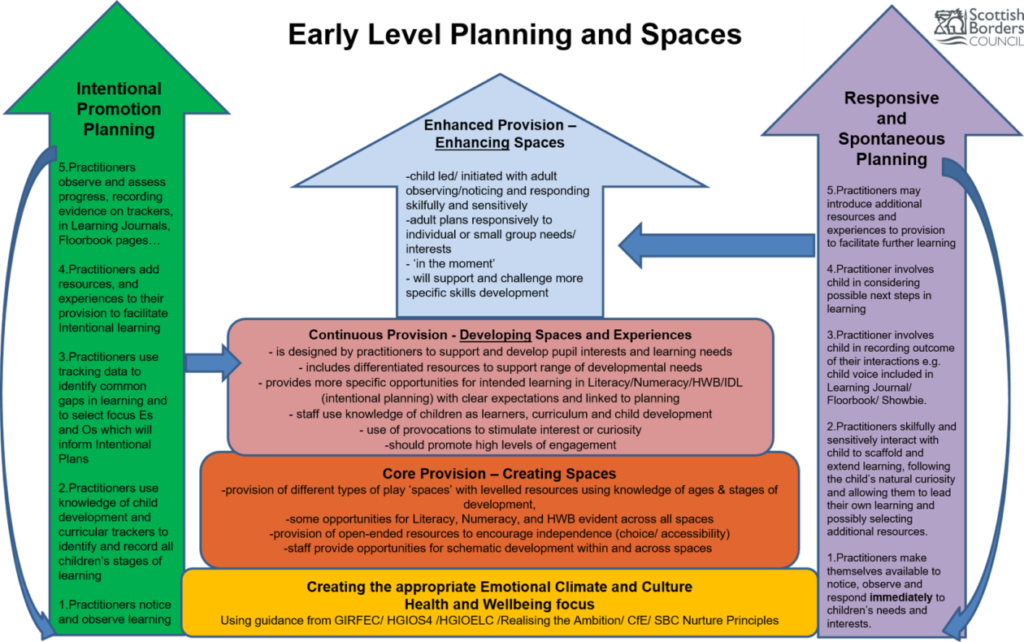

- Practitioners create purposeful experiences and meaningful contexts to facilitate learning responsively through child-initiated and adult-initiated play. Observations and interpretations of children’s play inform planning either in the moment or over a more extended period.

- Practitioners use their knowledge of the curriculum and child development to identify the next steps in learning for the child.

- Evidence should demonstrate progression for each child’s achievements both within the setting and beyond the gate.

- Practitioners use trackers (see tabs at the bottom of the Emerging Literacy & Mathematics & Numeracy pages) to identify children’s progress through responsive experiences.

- Practitioners use measures such as the Leuven Involvement Scale to monitor children’s level of engagement and use this to support planning.

- Responsive planning is found within learning journeys and Floorbooks, demonstrating child voice and the practitioner’s role in facilitating the learning (making learning visible and Sustained Shared Thinking).

Ways we can do this:

Knowing the child as a learner: Practitioners spend time observing children as they play to develop their knowledge of the child. This means that practitioners know children’s strengths and areas for development, where each child likes to play, who with and how they like to play. In addition, they consider their interests, family and cultural experiences, and their previous knowledge. This information is used to inform the planning of the environment and experiences.

Physical learning environment: Responsive planning is supported through quality learning environments. “Thought needs to be given to the opportunities that different learning spaces provide. Observe how the children use and interact with the outdoor and indoor spaces available and respond to their actions” (Education Scotland, 2020, p. 46).

Review the continuous provision to ensure accessibility for all developmental stages, e.g. resources to support schematic play, differentiated resources to promote emerging literacy, early numeracy and all skills across the curriculum. Also, see auditing tools to support enhancements to the continuous provision and City of Edinburgh, Planning with Children Document, 2016.

Using evaluative tools such as the Leuven Involvement Scale can help identify the levels of involvement for specific areas of the play environment. If low levels of involvement are identified, practitioners should consider the reasons for this and make appropriate changes. For example, consider including a wider range of resources that the children can explore independently in the art and craft area. Practitioners should consider if the play areas are inviting, accessible and create a sense of ‘wonder and awe’.

Quality interactions: Responsive planning is supported through quality interactions with practitioners. Practitioners spend quality time interacting with the children through child-initiated and planned play experiences, looking for possible teaching moments to extend learning.

Practitioners are aware of and value the many different ways they help children learn.

“Teaching… is a broad term that covers the many different ways in which adults help young children learn. It includes their interactions with children during planned and child-initiated play and activities: communicating and modelling language, showing, explaining, demonstrating, exploring ideas, encouraging, questioning, recalling, providing a narrative for what they are doing, facilitating and setting challenges.”

(Teaching and play in the early years – a balancing act?, OFSTED Inspection Handbook, 2015, p. 11)

Practitioners use their knowledge of the curriculum and child development to identify appropriate next steps in learning either in that moment or longer term. The use of developmental overviews, trackers and progression documents can facilitate this (see tabs at the bottom of this page).

Planning tools: Alongside intentional promotion planning, practitioners should have a format to record their role in responsively supporting learning and its outcome for children. This provides a snapshot of playful learning from across the week that has been facilitated by skilful practitioners. This should be reviewed retrospectively to identify which curriculum areas have been reached through these playful experiences.

Floorbooks can also be used as a method of documenting responsive planning. These may stem from adult-initiated or child-initiated activities. Practitioners record this process to tell the learning story and the children’s involvement. Summative mindmaps can be used to show all the different lines of enquiry that the children have been exploring and the experiences they have had along the way. These can be cross-referenced with the experiences and outcomes and monitor how well the curriculum is being covered.

Learning is shared with parents through documentation of learning such as Floorbook pages, learning journeys, Showbie (or similar e-journals) or closed social media channels.