![]()

Early Learning & Childcare for 2 year olds (ELC 2)

(ELC 2 bite-sized training videos )

What is this?

“Two year olds are undoubtedly a very special group. While all groups of children are interesting, I think that there is something particularly extraordinary about two year olds. Their development can be spectacular with most children moving from two-word utterances to speech that is in simple sentences and fairly clear and imaginative. This development is not automatic. It is more likely to occur when they are being supported by knowledgeable, nurturing adults… great thought and care is needed if two year olds are to flourish in our settings. Contrary to the views of some… they are not just shorter versions of three year olds! They think differently, play differently and this is what makes them so special.”

(A Penny Tassoni Handbook: Getting It Right For Two Year Olds, Tassoni, 2014, p. xii)

“When the baby starts to be mobile their world changes and the desire for independence increases.”

(Realising The Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 20)

“The toddler years are when your child develops from a dependent baby into a person in their own right. It can be a confusing time for you both.”

(Ready Steady Toddler!, NHS Scotland, p. 5)

“Being two is not easy. At times you feel big and strong. You declare your independence in all kinds of ways; you want to be respected and given space. Other times you feel small and vulnerable; the world looms large and scary. You want to be held and hugged and treated like the baby you used to be. Sometimes your special grown-ups just don’t get it, and then you fly apart!”

“The brain of a toddler is fizzing with activity. But all this activity is happening in a brain not yet equipped to make sense of it. In the second and third years of life the brain is still developing very quickly but this development is now focused on organising all the frantic activity going on in the toddler brain.“

(Tuning in to Two Year Olds, Improving Outcomes for Two Year Olds, Harrow Council, 2014, p. 3 & 4)

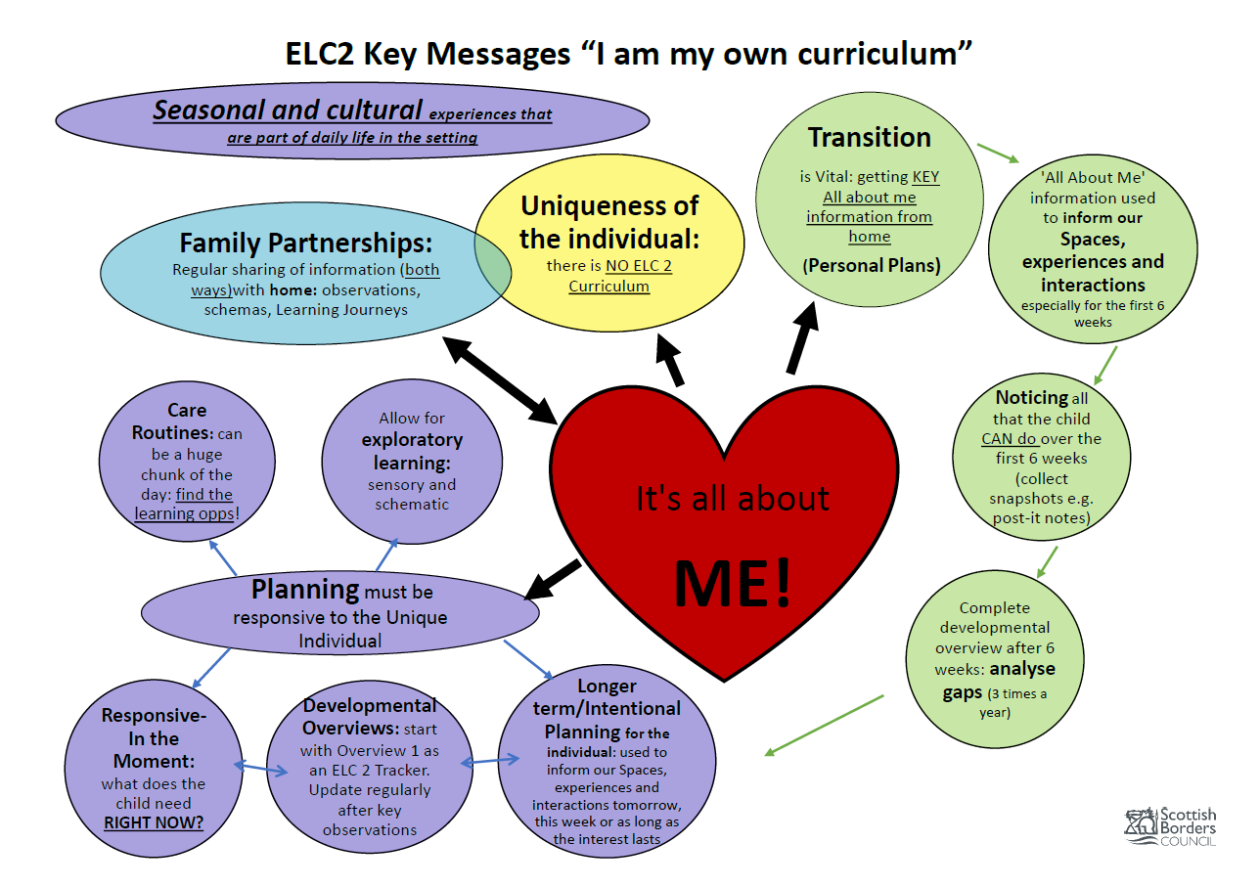

Key messages:

Transitions

-

- A detailed transition process is in place

- The transition into the setting is personalised for each child and family

- Key practitioners build relationships with children and families before starting at the setting

- Information from Care Plans and ‘All about Me’ is used effectively to support an individual child transitioning into the setting

- Spaces and resources reflect the children’s interests and needs

- Individualised measures are in place to support children through mini transitions throughout the day

Attachment

-

- All practitioners have a good understanding of early childhood development and the nurture principles

- All practitioners treat each child as a unique individual

- Each child’s needs are at the centre of how practitioners think about and plan for their unique development

- Practitioners understand that connection and attachment are fundamental

- Practitioners provide the support that is unconditional, continuous, reliable and predictable

- Key practitioners are in place to support, encourage, and care when children find frustrations and contradictions that make their world unpredictable.

- Key practitioners recognise the importance of the welcome, handover and reunion at the end of the session

- Practitioners are aware that secure attachments help children develop as confident individuals, successful learners, effective contributors and responsible citizens

- Practitioners understand that when young children feel confident, they find it easier to get along with others; feeling secure allows them to explore and investigate the world around them (GIRFEC)

- Practitioners know that secure attachments enable young children to cope with change and challenges. This is commonly referred to as resilience, which develops through positive relationships with kind and caring adults

Communication and Language development

-

- Practitioners understand that young children have problems explaining their feelings; this can lead to challenging phases requiring sensitivity and understanding of their conflicting needs, balancing this with the need for independence, risk, reassurance, and support

- Practitioners understand the role communication and language development plays in managing behaviour and emotions. Practitioners can reduce uncertainty by understanding and using patterns and cues for interaction, sequencing thoughts, and helping children understand what is happening and what might happen next

- Practitioners are aware of and use the Speech and Language Therapy’s Wee Talk Borders Chatting is learning – keys to communication handout

- Stories, songs and rhymes play a large part in everyday experiences and help the children recognise and understand their needs and those of others

Play

-

- Practitioners understand the critical stages of development in children’s play.

- Children have the opportunity to develop their confidence and practice their newfound skills in all areas

- Natural materials and open-ended resources support sensory play, exploratory play and creativity

- Practitioners celebrate success with the children

- Risk assessments around loose parts and smaller pieces of equipment are carried out regularly; practitioners include children in these experiences to help their understanding of keeping safe

Schemas

-

- The children’s desire for independence is supported; children’s own ideas and plans are encouraged as practitioners develop the environment to seek out the kinds of activities, resources, and encounters they need to help them develop

- Schematic play is understood, supported and responded to by practitioners. This information is then used to inform planning

Spaces

-

- When children’s interests are included within a well-planned and sensitively thought out learning environment, fostering and promoting a positive sense of self and wellbeing in young children

- Sensory experiences are offered daily, including opportunities for developing proprioception and vestibular senses

- Practitioners provide exciting things to do, see and talk about to spark curiosity

- Children might like to explore the nursery environments alongside their peers or siblings and not be confined to particular rooms designed for their specific age group

- Documentation of children’s learning around the setting is displayed for all to see and celebrate (learning journeys)

Routines

-

- Predictable routines are in place for big routines, e.g. rhythms of the day, small routines, putting on shoes and coats, and care routines where we have a ‘script’ for how things happen

- Familiar routines and experiences are in place to offer the children the confidence to explore further and take risks

- The child’s dignity is kept in mind at all times, especially during care routines

Self-regulation

-

- Practitioners support children to develop executive function, focus attention, remember instructions, filter distractions, and control impulses

- Practitioners support children with self-regulation, identifying and reducing stressors, encouraging self-awareness, helping children discover how to calm their own agitation and using co-regulation when required

- Practitioners remain calm and understanding when children display defiance, meltdowns, stubbornness, and fears, as they are all ‘normal behaviour’ for two-year-olds

Ways we can do this:

Transition

The setting evaluates and reviews its transition process at least annually. This is a whole team approach.

Transition is carefully planned and begins well before the child enters the setting, with keyworkers engaging with children and families.

Children and families know the names and faces of practitioners.

Families are made aware of the daily routines and transitions that their child will be supported with throughout the day.

The keyworker approach ensures that all children have a known adult to support them and their families during the transition process.

Attachment

“Relationships are based on respect, honesty and trust and getting it right to improve outcomes for children and families. We actively support our children to be safe, healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible and included. We can demonstrate the significant impact this has on our children’s social, emotional, and mental wellbeing as well as their development and learning.”

(A Quality Improvement Framework for Early Learning and Childcare Sectors, Sept 2025, p53)

All practitioners are engaging with Scottish Borders Council’s Nurture Programme.

Scheduling breaks, leave, and other situations when the key person may not be available is considered from the child’s point of view.

Practitioners have sound knowledge of the child as an individual, allowing them to find a balance between providing the child reassurance and support whilst participating in a range of play opportunities, respecting their need for independence.

Practitioners become the “secure base” for the child and know how their key children ‘check-in’ with them throughout the day. The children will explore and investigate if they know you are always there for them when needed. Practitioners use facial expression and body language to attune to key children and offer guidance and boundaries.

Practitioners can support the development of resilience for the children by providing safe and secure routines that children understand and are fully aware of. By having specific barriers and boundaries for children that they can understand, key adults create a feeling of trust.

Communication and Language Development

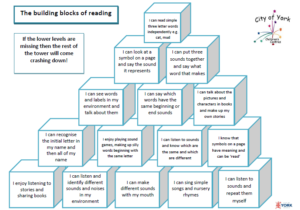

All practitioners have engaged with Scottish Borders Council’s Emerging Literacy Training.

Conversation skills are developing at this stage, and this growing vocabulary, including different types of words and sounds, is encouraged through:

- Stories

- Songs

- Rhymes

- Using simple language

- Short instructions

- ‘Doing the voices’ when reading stories

- Or, by providing a narrative (using words to describe what the child is doing).

Children should experience a wide range of daily opportunities for being read to, singing nursery rhymes, reading and telling stories together, as this creates opportunities for lots of chat.

Practitioners scaffold children’s learning and give them opportunities to rehearse and consolidate independently. In addition, books are available that promote children’s engagement with recalling words, sentences, and rhymes.

Practitioners enhance the learning experience and maximise opportunities for developing verbal skills. They carefully introduce new things, e.g. foods, places, people, and ideas. It is usual for a two-year-old to be shy or reluctant at first. Practitioners model what to do and give children space to explore and develop confidence.

“Eating together affords the chance for children to develop language and communication skills in a meaningful social context. From a very young age, babies and children learn turn-taking, the importance of eye contact and gesture in communicating needs and wants. Young children practise sharing and become aware of each other’s personal space and points of view; these skills are crucial to effective communication.”

(Realising the Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 58)

Play

Practitioners are aware of and resource the environment to allow for the developing stages of play that are emerging at this age, recognising that they may need repetition and consistency.

developing stages of play that are emerging at this age, recognising that they may need repetition and consistency.

Practitioners encourage the awareness of others, supporting children as they play alongside each other and start to play together. They are encouraged to be ‘socially comfortable’ and helped to ‘read’ the messages others may give, e.g. being happy, sad or upset.

The increased capabilities of younger children through learning and having fun alongside the older children is recognised, as it provides further opportunities for children to widen their friendships.

Practitioners carefully observe play, knowing when best to stand back and when the child would be receptive to more support.

Practitioners understand that it is unrealistic to expect a very young child to sit and engage with some of the resources the same way as an older child. However, that does not mean that the playful adult cannot intervene and support mixed-age play.

Schemas

Practitioners observe the children noting repeated patterns of behaviour, including throwing, climbing or moving things from one place to another. They then use this knowledge to organise resources and activities to support and extend these behaviours.

Practitioners use knowledge of schemas when making observations of children and as a basis for planning and resourcing environments.

Practitioners share information effectively on schematic play with families, using Education Scotland resources.

Spaces

The emotional environment is warm, and the children feel safe. Pictures of the children’s ‘family’ (important people, animals in their life, etc.) are included where possible.

Piaget (1951) said, “A child’s development is directly linked to its ability to interact with its environment. Children develop an understanding of themselves through their interactions with events and materials outside themselves.”

Practitioners value each child as a unique individual, rich and resourceful, regardless of their age and stage of development. To make this visible, playrooms could be mixed age to support peer-led learning and increase the capabilities of the younger children. This would allow children to widen their friendship groups and develop leadership and empathy skills for older children.

The environment is a rich and resourceful learning environment. It supports a wide range of learning opportunities, evident in how children take their own learning forward. Practitioners react in a responsive way to children’s learning and individual interests, with breadth, depth and challenge opportunities available in every area.

Practitioners create an ‘enabling’ environment, recognising that children gravitate towards ordinary everyday objects rather than manufactured toys. These experiences can be more sensory and stimulate more significant levels of creativity. Provide real-life objects, stimulating environments, and notice the small wonders while talking with the children. Heuristic play experiences are planned to support children (see Elinor Goldschmied’s work on treasure baskets and heuristic play).

The interactions that practitioners have with the children are respectful. Children are listened to, and their voice is visible throughout the environment.

Documentation of children’s learning around the setting highlights the high level of collaborative learning when children share their specialised skills with each other (learning journeys). Role-modelling of positive behaviour and partnership working is celebrated and documented for all to see.

The documentation approach makes children’s learning visible. It allows practitioners to record what children are saying and emphasises that this is their setting.

Loose parts need to be regularly checked for damage, e.g. small pieces that may have broken off and could be a choking hazard, sharp edges etc. Children can be involved in these conversations, helping them understand how to keep safe and carry out risk assessments.

Spend as much time as possible outdoors. This is where most two-year-olds are often at their happiest. Being outdoors also helps with appetite and sleeping. Get out and about! Once children have got the basics of walking, the next stage is to develop balance and stability.

Routines

Practitioners understand the holistic benefits of care routines to children’s overall development and recognise daily routines are a rich opportunity to promote close attachment.

Practitioners try to keep a routine so that two-year-olds understand what happens next and what they need to do.

“Routines such as meal times, rest times and personal hygiene should be viewed as learning opportunities where we take time to support and encourage children to learn necessary skills for life.”

(Realising the Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 57)

“Our nurturing approaches ensure that children develop positive attitudes towards change and show determination to succeed in their chosen experiences. All our children are supported to develop the skills, confidence and motivation to initiate and participate in improvements to our setting and community.“

(A Quality Improvement Framework for Early Learning and Childcare Sectors, Sept 2025, p36)

O’Sullivan and Chambers (The Twoness of Twos: The Leadership for Two Year Olds, 2014) say

“Children need to have an orderly routine that provides structure within an environment that is dynamic and changing but also predictable and comprehensible!” (p. 12)

“When two year olds were regularly involved in small group experiences, they were more able and more confident at participating, thus enabling their ‘voices and feelings’ to be acknowledged.” (p. 9)

Practitioners encourage independence at snack and mealtimes; this can require patience, time, lots of positive encouragement, and reinforcement.

Practitioners should use visual timetables to help two-year-olds allowing plenty of time for transitions.

Sufficient time is allowed for each care activity, considering what the children see or hear during their care routines.

Care routines are seen as an opportunity for meaningful interaction. Children can exercise some degree of choice or control during each care activity, and support is delivered with kindness and compassion.

Most two-year-olds will still need quiet time or a nap, which can significantly affect their mood and ability to cope with frustration. Sleep routines reflect individual children’s needs and family wishes and promote good habits around sleep.

Make sure you have the child’s attention, e.g. getting down to their level, using their name, give them time. If they find transitions difficult, give notice well before the change; for example, if it is time to stop playing and they are very engaged, explain what is due to happen, giving them plenty of warning. Practitioners can refer to a visual timetable, reminding them when they can return to this activity later.

Practitioners help children understand how they might be feeling, what they can or cannot do, and give the child some control, e.g. they will tidy up, but may decide where to start or who to work with.

If children are exhibiting distressed behaviour, practitioners try distraction, remembering to look relaxed while offering a gentle touch if the child can accept it.

Sometimes what children really want is to be held and contained, go down to their level and offer a cuddle.

Self-regulation

Children can depend on an adult to be physically and emotionally available, attuned to co-regulate their strong and wide-ranging feelings and emotional expression.

Practitioners understand that two-year-olds are not trying to be difficult on purpose. Instead, they are just beginning to gain control of their movement and actions but cannot always make their needs and wants understood.

Practitioners model social behaviours such as inclusion, sharing, and promoting acts of kindness through encouragement and praise.

Practitioners help the children develop the skills or experience to manage strong feelings, e.g. fear, hunger, happiness, anger, helping them stay safe and get through the day in a calm way ‘naming and taming’ their emotions and feelings.

Practitioners are consistent when children push boundaries or ‘test the waters’, explaining the potential consequences of their actions and why they should not continue.

Big emotions are going on at this age. Practitioners take time to really listen, make them feel understood, and model how best to express these emotions.

Practitioners understand the best rewards for a young child are praise and cuddles.