Independence

What is it?

A child’s confidence and self-esteem develop as their independence grows, fostering self-reliance and resilience as they face new situations; there is a growing feeling of, “I can do it on my own.” Independence encourages children to be sociable, more self-aware of their peers and sensitive towards others. It teaches them to be self-motivated, become better decision-makers, and master new skills. It provides them with the belief that they are competent and capable of taking care of themselves, now and in their future adult lives and workplace.

As it states in Realising the Ambition (Education Scotland, 2020):

“…we need to be confident that in promoting a happy, interesting and empowering learning environment, considering the interactions, experiences and spaces on offer, we as practitioners add value to what children already know and can do” (p. 15).

“Everything we do in ELC and early primary should be about helping the child grow emotionally, socially, physically and cognitively” (p. 15)

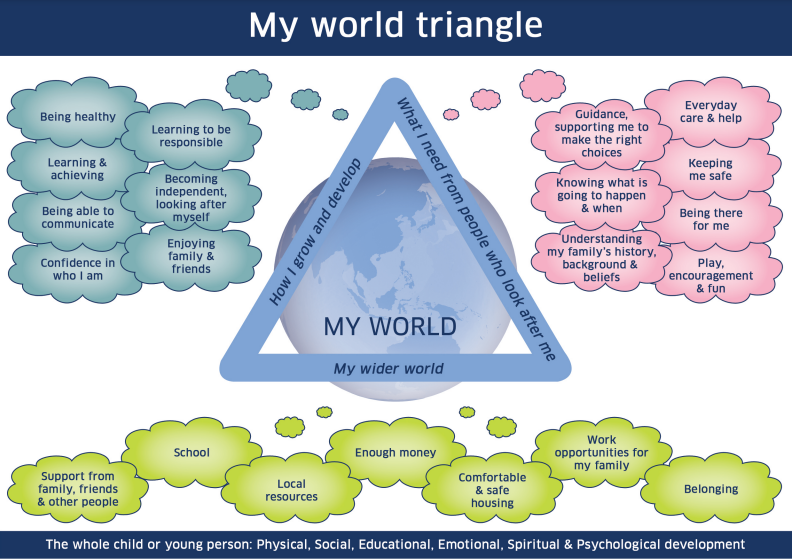

The Scottish Government says, “Curriculum for Excellence provides young people in Scotland with skills for learning, life and work so that they can lead healthy and fulfilling lives and take their place in a modern society and economy. Getting it right for every child is how we can all work together to ensure that every child and young person can be the best that they can be.”

“Learning through health and wellbeing promotes confidence, independent thinking and positive attitudes and disposition. Because of this, it is the responsibility of every teacher to contribute to learning and development in this area.”

(Getting it right for every child: A guide to evaluating wellbeing in schools and nurseries, Scottish Government, p. 17)

This includes supporting children to become more independent.

Key messages

Interactions

“Me as an individual. Each child’s needs should be at the centre of how we think about and plan for their unique development. Children have their own ideas and plans, and their brains and bodies are good at seeking out the kinds of activities, environments and encounters that they need to help them develop.”

(Realising the Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 15)

- Practitioners adapt their interactions to support the uniqueness of each child’s needs.

- Children know when help is needed and how to ask for it.

- Children have a positive attitude to learning (confident individuals) and learn how to learn.

- Skilful adults engage children in conversations about their learning (effective contributors).

- Practitioners show ‘professional love’ and develop positive, trusting relationships with all children.

“Much of what children learn in the first few years, they often discover naturally for themselves, in their own way in their own time. For this development to be successful, babies in particular need to know their caregiver is nearby and that the support they provide is unconditional, continuous, reliable and predictable (O’Connor 2018)”.

Realising the Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 15

- Nurture principles are embedded in practice.

- Practitioners establish supportive relationships with families and communicate effectively to best meet the child’s needs. The transition process allows practitioners to develop relationships with the children and families before entering the setting. Transition information is used effectively to support individual needs from day one.

- Practitioners respect and value the children’s rights and help them understand this in a developmentally appropriate way.

Experiences

- Practitioners demonstrate a sound understanding of early childhood development.

- Children are enabled to choose where to play, with who, and when.

- Practitioners use the wellbeing indicators to consider the needs of individual children and ensure their needs are being met.

- Practitioners model and support children to become independent through positive and encouraging language during their everyday interactions.

- Daily routines, e.g. snack, lunch, personal care, transitions indoors/outdoors and to/from the setting, are well established with clear and consistent expectations that support the needs of all children.

- Practitioners recognise and celebrate the success and progress of individual learners (within and out with the setting).

- Children are ‘mind-minded’ and aware of themselves as learners (successful learners).

- Children are given responsibility (responsible citizens) and are independent in self-care routines.

- Children are engaged in deep and meaningful learning and are involved in ‘leading their learning’.

“Moyles (2015) argues play pedagogy values children’s contributions to their own learning and offers opportunities for children to take ownership of their learning.” (Realising the Ambition, Education Scotland, 2020, p. 47)

- Children are aware of their emotions and are supported to understand these in a developmentally appropriate way. All practitioners use agreed techniques or strategies to help children with self-regulation.

Spaces

- Learning spaces promote curiosity, creativity, and problem-solving enabled through open-ended resources.

- Learning spaces are carefully created to offer differentiated resources to meet all children’s developmental stages and needs.

- The child’s voice is visible throughout the setting.

Ways we can do this:

Interactions: Practitioners take time to get to know each child and their individual interests, developmental stage, strengths, and areas for development. They respect and nurture each child as an individual. They communicate with parents and use this information to inform their knowledge of the child, e.g. personal plans.

Practitioners understand and support schematic play.

Practitioners understand and recognise learning dispositions (learning powers) (e.g. perseverance, resilience, co-operation, imagination), helping the children understand them through using comments such as, “You had to concentrate hard to do that!”, “Well done for trying,” “Have a go!”.

Practitioners wait, watch and wonder, using ‘sensitive interactions to intervene skilfully to support, deepen and extend the child’s understanding.

Practitioners explain, model and encourage children to respect belongings, each other, and be kind and stay safe (the Wellbeing Indicators).

Practitioners support the development of children’s thinking skills through scaffolding, modelling, questioning and making their own thinking explicit.

Practitioners understand the importance of non-verbal and verbal communication and view all types of communication as behaviour.

All practitioners are engaging with the SBC mandatory nurture training videos. See Nurture for video links.

Practitioners are approachable and communicate effectively with families in different ways, e.g. social media/virtual platforms (Showbie, Microsoft Teams, closed Facebook groups, Twitter, etc.), newsletters, daily contact at drop off and pick up, formal parent meetings etc.

Experiences: The transition process is regularly reviewed and adapted to meet the needs of each child and family.

Transition visits and information familiarises children with practitioners, the physical environment, important routines and mini transitions they will experience throughout the day. As a result, children know what to expect when they enter the setting.

Transition information (including meetings and personal plans) from home allows practitioners to identify needs and prepare the environment to support the individual child.

Practitioners work closely with other professionals to ensure the correct support is put in place when necessary to meet the needs of a child.

Children have the freedom, choice and undisturbed time to play, explore and investigate with a range of natural and open-ended resources. This will motivate children to explore and investigate through play, including taking calculated risks and learning from their mistakes.

Practitioners encourage children to take responsibility within their play, e.g. self-selecting and accessing resources, organising resources and spaces, setting the table, self-serve at snack/lunch. Practitioners should also consider the room from a child’s level, the visual and written cues and labels, and self-registration.

Practitioners encourage and support children to become involved in self-care routines, e.g. toileting, dressing, eating, helping to tidy up after meals, until they can be self-sufficient. If children experience the same daily routine, they learn to take more responsibility and want less help.

Children can use their emerging literacy skills to express their needs and wants and follow the steps in routines with increasing confidence.

Children have a good understanding of their rights and can talk about them. UNCRC and an effective children’s rights-based approach should be embedded in the setting’s ethos, routines, and change implementation. It should not be ‘another thing to do’ but already underpin the setting’s pedagogy and be part of the practice, e.g. learning journeys, observational language, Floorbooks, learning stories, GIRFEC, consistent rights-based language across the setting used by all stakeholders.

Practitioners use learning journals and Floorbooks to involve children in discussing and recording their learning.

Practitioners understand and use developmental overviews, emerging literacy trackers (see tabs at the bottom of the Emerging Literacy page) and the SBC Mathematics & Numeracy Early Level Tracker (see tabs at the bottom of the Mathematics & Numeracy page) to plan and track individual progress and identify gaps in learning. In addition, all practitioners should engage with SBC training to support effective implementation.

Practitioners actively engage with up-to-date and relevant training and put this into practice in the setting.

Spaces: Practitioners use their observations and knowledge of child interests and developmental stage to set up provocations that provoke interest and curiosity.

Resources are natural and open-ended to provide opportunities to develop problem-solving, curiosity, and imagination.

All practitioners support children to follow routines, e.g. ‘visual timetables’ or photos of the children to show sequence of events, clear, simple and consistent instructions and modelling. If children can anticipate their day and experience the same daily routine, they learn to take more responsibility and want less help.

Practitioners use various resources to support children in understanding and expressing their feelings, e.g. stories, songs, photos, emotions board, offering a range of strategies to support self-regulation. Wellbeing indicators can help this.

Practitioners use observations and information from parents to recognise and celebrate individual successes, e.g. ‘Wow moments’, learning journeys, learning walls, etc.

Practitioners use audit tools, e.g. the Leuven scale, monitoring engagement and well-being levels, to evaluate their spaces and experiences based on what they observe.

Linked Areas of Practice

Child Development

Child’s Voice

Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC)

Inclusion

Lunch/snack times

Personal Plans

Risky Play

Tools

Reflecting on Practice

SBC Guidance to support

National Guidance to support

Further Reading to support

Training to support