In a recent Mathematics and Science input, we were very fortunate to be visited by guest lecturer Brenda Rochead who works for the Scottish Financial Education Group. The input focused on how we can raise financially capable children in a society rife with poverty and undesirable financial situations through education starting in the early years. Her input, along with a related workshop, really challenged my views on financial education and children’s capacity to learn about finances and I wanted to record my new ideas within this post.

Personally I would say I handle my finances reasonably well. I have a part-time job while I study at University to fund living costs, I treat myself occasionally and socialise regularly and I try to save money when I am able to do so, however I do wonder how my financial status and attitude would differ had I been taught about money when I was at school. The 5-14 curriculum that I was taught under, did incorporate what I would now refer to as, “money education”. I was able to identify a variety of coins and notes; I could count the correct coins to pay for items; I was able to calculate change however if you asked me to read a bank statement or describe credit, even as a young adult, I’d find it incredibly challenging. Prior to the input with Brenda, my teaching strategies regarding financial education would have reflected similar approaches used while I was at primary school – for example, manipulating coins during role-play in a shop scenario and calculating the appropriate change. However following the input this attitude was completely changed. Although this is an essential skill, I believe we are limiting our pupils to this and almost creating a ‘purchasing ethos’ where money only concerns buying. Instead I believe we should be building financial resilience within our pupils introducing them to real life scenarios, developing life skills and preparing them for their unpredictable financial future.

So how do we build financial resilience within our youngest pupils? As highlighted by Brenda during the input, we should be addressing skills, knowledge, attitude, motivation and opportunities. By skills I refer to financial literacy – the understanding of how money works in the world: how we are able to make or earn money; how we manage money and how we can turn this into more through investment. With this in mind we should be teaching our pupils how to read bank statements to develop an awareness of spending and saving; discuss employment and develop entrepreneurial skills; introduce skills such as taking money out of an ATM machine and the necessary safety precautions or how to use online banking etc. The additional knowledge children should acquire through financial education includes, but is not limited to, the dangers in the financial world such as debts and online safety and where you are able to receive help should you find yourself in an undesirable situation. Furthermore we should be promoting a ‘need vs. want’ attitude when it comes to spending money and encouraging pupils to save money for later in life when they will need it most.

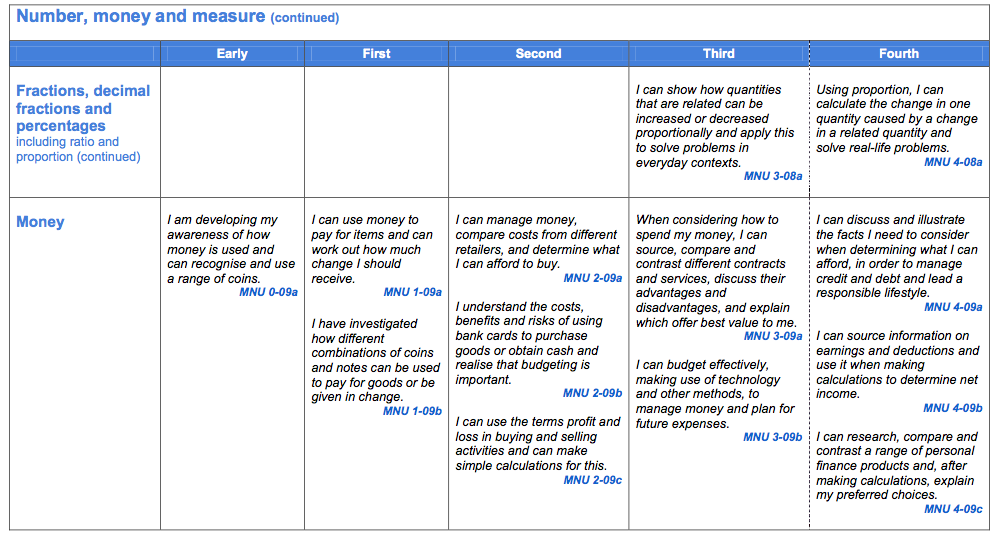

In early and first level, Curriculum for Excellence highlights the importance of manipulating money and the word “used” is very apparent within the experiences and outcomes. Without the addition of building financial resilience within the early years, we risk exposing our children to the “purchasing attitude” I mentioned earlier. Within second level, we begin to see the phrases “manage money”, “understand risks”, “budgeting” and “profit”. However I believe we should be exploring these earlier on in schools to encourage pupils to think further than how much it will cost to buy a Freddo after school!

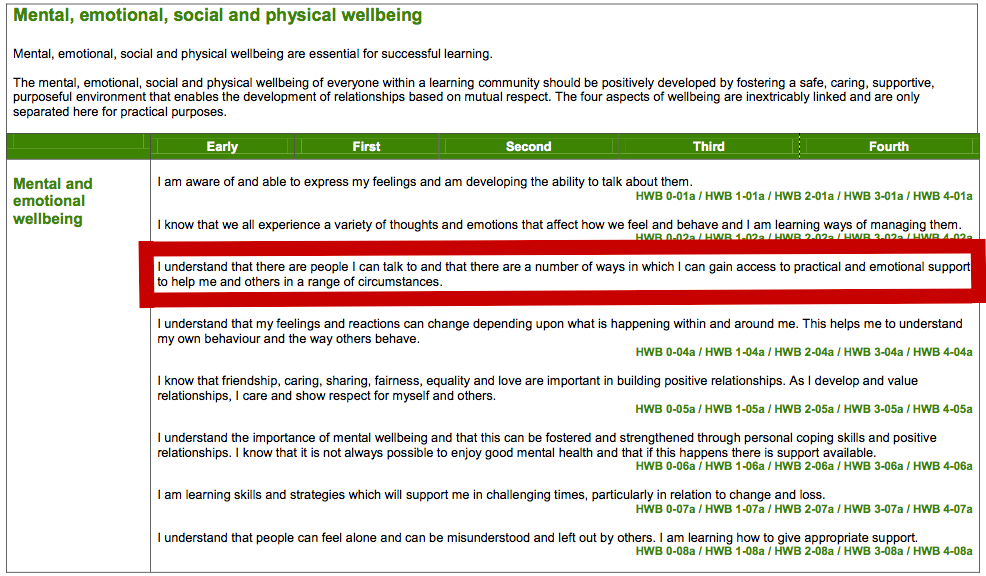

Raising financially capable pupils is not just apparent within the Numeracy and Mathematics curricular areas. For example, the Health and Wellbeing experiences and outcomes touch on emotional and mental wellbeing which correlates directly with the pressure of finances. However the need for more emphasis of finance within CfE is apparent and Learning and Teaching Scotland released a document in 2010, that highlights the rationale for embedding more structure of this particular subject into the curriculum. “The philosophy and practice underpinning Curriculum for Excellence offers many opportunities for children and young people to experience financial education. Financial education will provide a relevant context to develop knowledgeable, skilful and enterprising children and young people who can take increasing responsibility for their own lives and plan for their future (p9).” By encouraging pupils to think about managing their money, we are creating responsible citizens and effective contributors to society, two of the four capacities highlighted in CfE.

Within their document, Learning and Teaching Scotland highlight a number of ways children can be involved in financial education. These include having a whole school credit union, running a money week and getting involved in fundraising (See the full document here). However like the CfE experiences and outcomes, I see this as an upper stage activity, where although the early and first level pupils could be involved, the responsibility would primarily fall to those in P6/P7.

So how can our EY pupils get involved in financial education? Play is an important part of EY learning and provides plenty opportunities for children to explore money beyond the traditional British Stirling coin set. Creating a Bureau de Change Role Play area would be a fantastic opportunity for pupils to explore different currencies and learn how to convert money. Alternatively a Travel Agent area would be a perfect opportunity to look at deals when travelling abroad and how to save money for trips on holiday.

Children often observe their parents when they are stood at an ATM machine or talking to accountants in the Bank so they could use this experience and act out these scenarios. Using a box or screen, the children could create an ATM and perform the necessary actions to take money out whilst another pupil counts the correct money. This would also allow for discussion about safety when at the bank or ATM.

Taking your personal receipts for the pupils to explore would be an engaging activity for the pupils – they’d love to see what your bought for your tea on Monday Night and they would be able to observe the format of a receipt and identify offers within the print!

With all this considered, the most important things I gained from Brenda’s input was to think outside the box regarding learning activities and aim to stretch my pupils understanding of money beyond purchasing niceties. As teachers we want to ensure that our pupils are as prepared as they can be for society, so why are we limiting their experiences and their mind-set?

How would you teach your pupils to become financially resilient? What other skills to pupils need to manage their money? What other learning activities would be beneficial to enhance their understanding of how money works? See my financial education pinterest board for some ideas on EY financial education.

References:

Learning and Teaching Scotland (2010) Financial Education: Developing skills for learning, life and work. Available at: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/Images/developing_skills_web_tcm4-639212.pdf [Accessed: 28/01/16]

Scottish Government (2009) Curriculum for Excellence, Experiences and outcomes for all curriculum areas Available at: http://www.educationscotland.gov.uk/Images/all_experiences_outcomes_tcm4-539562.pdf