![]()

Sensory Processing (& integration)

What is it?

These are the systems our body uses to make sense of the world around us. We process information through our senses responding to the things we are experiencing.

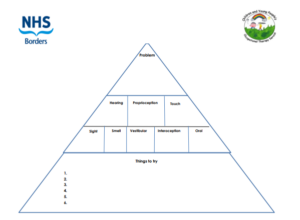

The main 8 senses are:

- Sight

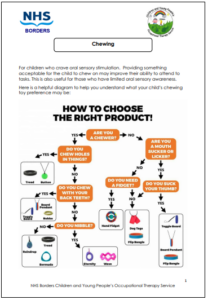

- Taste (gustatory)

- Smell (olfactory)

- Hearing (auditory)

- Touch (tactile)

- Proprioception (using our muscles to understand where our body is in space, i.e. tells us where our body is without looking)

- Vestibular (the sense of how the body moves against gravity, i.e. helps us with balance and movement)

- Interoception (how we feel inside, i.e. messages like hunger, temperature, pain etc.)

These last 3 lesser-known sensory systems: proprioception, vestibular and interoception, help us feel in tune with our world and to feel grounded and regulated.

Proprioception: This helps give a sense of where the parts of our body are in relation to each other and their surroundings. Our brains work this out using information from our muscles, joints, along with the sensation of touching things. Children need to develop this sense to support them with their movement, e.g. to help with feeding themselves, to understand the ‘space’ they take up when finding a space to sit in without sitting on top of or bumping into someone else, or how tightly they need to hold the minibeast, or when pressing the pen onto the paper.

Vestibular Sense: This lets us know if we are moving and, if so, in what direction and how fast. Information is gathered mainly from the balance organs deep inside our ears. We need to help the children develop this so they can move effectively and safely and balance and sit upright, e.g. when eating, riding a bicycle etc.

Interoception: A wide range of information is sent to our brain from all over our body, giving information about levels of hunger and thirst, when satiated, pain or illness, body temperature, tiredness, etc. This internal body sense also tells us about the changes in our heart rate, breathing, alertness and feelings like “butterflies” or a sinking feeling (often in our gut) which come with and signal strong emotions. We need to help the children understand and interpret these feelings.

While we all experience types of sensory input, we do not all experience these sensations in the same way. Some children will demonstrate strong sensory preferences, seeking a sensation as it is pleasing and regulating whilst others may avoid activities as the sensory experience overwhelms them or is unconformable to tolerate.

Processing sensory information as it comes in can be difficult for individuals who either seek out or avoid sensory input. Studies indicate that around 20% of school-aged children experience sensory processing challenges that affect their ability to carry out daily tasks. While sensory processing differences are more commonly associated with neurodivergent conditions, a diagnosis is not necessary to experience these challenges.

Typically, the brain is able to prioritise and filter sensory input, allowing us to ignore unimportant information—like background music or distant chatter—so we can focus on what matters. However, for some individuals, tuning out this background noise is difficult, making it hard to concentrate and often leading to feelings of overwhelm. Sensory processing experiences can vary greatly from one person to another. it’s important to be mindful of these differences, not only for our children but for ourselves and our colleagues.

“Sensory integration or as you will often hear it talked about sensory processing is something all living things do. In humans registering sensory information, modulating it, integrating it, and producing effective behavioural responses is part of everyday life. This ability helps to drive our development and enables us to adapt to the environmental demands of work, leisure, self-care, and care of others. For children it may be their learning, the play that they engage in and how they look after themselves.” NHS Borders Occupational Therapy

“Sensory issues can limit your child’s ability to interact with others, their environment, and their ability to perform meaningful tasks…Sometimes they may seek sensory input to make them feel better e.g. a cuddle. Sometimes they withdraw from sensory input such as very loud noises of bright lights because it makes them feel uncomfortable. We all do things to make us feel better, for a child it may be to play with a special toy or, be wrapped up in a blanket or watch a movie that they like.” NHS Borders Occupational Therapy

Modulation and Self Regulation

The central nervous system automatically interprets, organises, and processes sensory information without us even being aware of it. Sensory input is something the brain receives, processes, and then responds to.

When the brain gets too little sensory input, it may prompt the body to move more. This is often why children fidget. Many adults do similar things—like shifting in our seats, tapping a pen, or doodling on paper. This can help to help maintain our focus. These actions help keep our alertness at what we call the “just right” level. For children, fidgeting serves the same function: it helps them stay attentive and focused.

Conversely, when the brain is flooded with too much sensory information, it can trigger a fight, flight, or freeze response. For example, a child overwhelmed by the noise in a busy dining hall may become very distressed and need time in a calm, safe space to recover.

Struggles with processing sensory input can greatly affect a person’s alertness. NHS Borders Occupational Therapy Service promote a helpful way to understand this is by using the characters from Winnie the Pooh. The “Tigger zone” describes a state of over-alertness, where a child may be energetic, constantly moving, easily distracted, and possibly agitated or overly excited. The “Eeyore zone,” on the other hand, represents under-alertness, where a child might seem tired, sluggish, unmotivated, and have difficulty focusing.

Between these is the “Winnie the Pooh zone,” or the “Just Right” zone. When a child is in this zone, they are alert, focused, motivated, and ready to learn. Throughout the day, everyone moves through these zones and uses sensory strategies to help regulate themselves. For example, we might begin the day feeling low energy in the Eeyore zone and take a shower to wake up, or calm down from the Tigger zone by going for a walk or listening to music to return to that ‘just right zone’.

Children with sensory integration difficulties often benefit from adult support to develop and use these strategies, helping them stay in or return to the ‘just right zone’.

Key messages:

- Practitioners should access the NHS Occupational Health Website for support, training, ideas and resources and to ensure that they have a sound understanding of sensory integration.

- Practitioners have a clear understanding of the needs of children throughout their developmental stages.

- Practitioners have a strong understanding of sensory development in the early years and how to support children to regulate their sensory needs throughout the day.

- Every child should be seen as a unique individual. One child’s sensory preference could be overstimulating for another child. Children’s behaviour may look similar but it may be communicating different needs.

- Observe children and be curious about the unmet need behind the behaviour

- There are positive and respectful relationships between practitioners, children and families. Work closely with families to identify a child’s sensory needs and appropriate strategies. Families are often the expert’s on their children and their input should be valued.

- Sensory challenges are considered when setting up the environment, for example reduced clutter, reduced colour, reduced bright lighting, feel better spaces.

- Spaces are designed to reduce excessive noise, for example positioning the construction area on a soft surface.

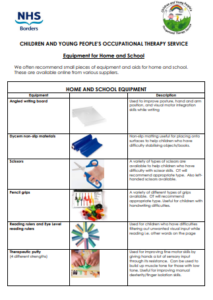

- Fidgeting is a way children self regulate, if a child is fidgeting this tells us that their brain is seeking sensory input. Practitioners should give children appropriate ways to meet this need rather than expecting the child to sit still.

- All practitioners use calm and respectful voices at all times and in all situations.

- There are opportunities to engage with and experience nature and the outdoors regularly.

- A range of sensory experiences are offered throughout the day and are embedded throughout the spaces and experiences.

- Practitioners support the development of self-regulation and executive function.

- Practitioners tune in to children’s interests.

- The practitioners know the child well and understand how to support interactions.

- Practitioners interact non-verbally when needed with individuals and respond to their non-verbal communication, e.g. sharing an experience, mirroring, parallel play.

- The practitioners work together to create inclusive, enabling, sensory friendly environments.

- Practitioners seek out further support if or when necessary.

Ways we can do this:

NHS Borders Occupational Therapy website and training videos

Sensory audits are carried out regularly to support developments.

Care Plan+ are used to share an understanding of the best ways to support the child between home and settings. Primary caregivers are invited in to work together on writing the Care Plan+.

Practitioners co-regulate with children. All practitioners should complete the Self Regulation training on the Early Level Portal.

Opportunities for sensory development are embedded throughout children’s spaces and experiences. Such as sand, slime, water, being outdoors and messy play. considerations are made for those who may find these experiences challenging, for example having gloves or tools available for messy play.

Use contrasting tactile experiences, for example incorporate sand or shaving foam together in the same learning experience.

Children should be given opportunities to move as much as possible. Young children should not be expected to sit still for prolonged periods of time. In ELC children should be invited to sit for group times but not forced to. As it becomes necessary for children to join teacher directed tasks and carpet times, children should be given regular movement breaks and accommodations made if the child needs to more. for example chair sit-ups, fidget toys or wobble cushions.

Practitioners are curious about the needs of individual children and use observation to help identify triggers, predict patterns and put effective strategies in place. Keep a record of the child’s arousal levels at various times, notice how the child behaves and consider what sensory systems may be involved.

Avoid light touch as this is more alerting to children’s sensory systems and can be uncomfortable and in some cases painful. Always use positive touch on the child’s terms. Use firm pressure if touch is required and always ask for consent.

Calm, respectful voices are used in all situations; being respectful is one of the eight indicators of wellbeing, which are vital to ensure that children grow and develop and are given the best possible outcomes for their life chances and wellbeing. Loud voices can be overstimulating and uncomfortable for some children.

Areas are designed with sensory preferences in mind, ensuring that there is not excessive colour, light, noise or clutter.

Quiet spaces are available for children who need a break from the sensory overwhelm of the main spaces. Sensory baskets could be used here for optional ways for children to meet their sensory needs e.g. paint brushes, sponges, glitter bottles.

Give regular opportunities for heavy work, heavy work is regulating for children and can give them the proprioceptive input they are seeking throughout the day. for example lifting large blocks, digging, carrying buckets, moving tyres.

Take time to thoughtfully consider any adjustments that could improve the lunch experience. Children may encounter many different sensory inputs in the dining hall. These might include the noise of conversations, the clinking of forks and knives, sounds of slurping, crunching, or chewing, as well as the smells of various foods. They might also feel physically uncomfortable sitting on a chair that lacks proper support or is the wrong size. Additionally, the sight of numerous people moving around them can be overwhelming.

If necessary, practitioners seek further support, e.g. CPD courses, professional reading, SMT input, and specialist services.

The NHS Borders Children & Young Peoples Occupational Therapy Service, offer a needs led service. Once you have tired all of the strategies available on the website, the OT service may be able to offer further, more bespoke support for children.

Examples of behaviours that may indicate sensory processing needs:

(Many of these behaviours are not uncommon, but sometimes they can be persistent and impact on quality of life)

Running out of busy places with lots of visuals and/or sounds present: This may be a child who cannot cope with processing different things all at once.

Seeking lots of physical movement throughout the day: This may be a child who needs more information into their muscle and movement systems to tell them where they are in space.

Sensitivity to light touch: Your child may be very sensitive to unexpected or light touch and have an anxious response to it.

Seeking heavy touch and hugs: Your child may seek heavy contact, for example, through hugs, to get more input to their touch system. This can be calming for them.

Difficulty with posture and coordination: This may represent a child whose muscle and movement systems are not as efficient.

Being overloaded by visual or sound input: This may affect their ability to concentrate.”

NHS – Sensory Processing in Young People with a Learning Disability and/or ASD

Children with Autism may display sensory processing/integration issues, however all children process their 8 senses differently and will have different tolerance levels, needing more or less stimulation to satisfy them.

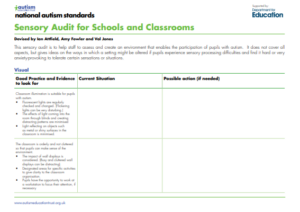

Sensory Audit Tool – Education Scotland

Sensory Audit Tool – Education Scotland