Neurodevelopmental differences

Neurodiverse groups may include individuals with a range of neurodevelopmental differences, such as:

- Autism

- Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Developmental Co-ordination Disorder (DCD) also referred to as Dyspraxia

- Developmental Language Disorder (DLD)

- Epilepsy

- Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

- Intellectual Disability

- Tourette’s and Tic disorders

- Specific Learning Disorder/ Differences e.g. Dyslexia, Dyscalculia.

It is normal practice for learning differences such as Dyslexia and Dyscalculia to be identified through a non-medical pathway.

It is rare that a child or adult would have only one area of difficulty. Co-occurrences of learning differences are very common.

Needs, not labels

According to the The Additional Support for Learning (ASL) Act, support must focus on needs. It is not dependent on a label or diagnosis. The vast majority of children and young people in Scotland are supported in the Universal level of the Staged Level of Intervention. This uses a universal approach and enables the development of learning and teaching which is accessible for all learners.

According to the The Additional Support for Learning (ASL) Act, support must focus on needs. It is not dependent on a label or diagnosis. The vast majority of children and young people in Scotland are supported in the Universal level of the Staged Level of Intervention. This uses a universal approach and enables the development of learning and teaching which is accessible for all learners.

Ableism

When working with children, it’s important to remember that the goal is not to train them to fit into a predefined idea of what is “typical.”

Instead, we should focus on supporting each child’s unique learning journey. Our role is to be curious about the diverse ways children play, think, and communicate. Rather than asking children to adapt to our expectations, we should adapt our approach to better understand and support their natural ways of being.

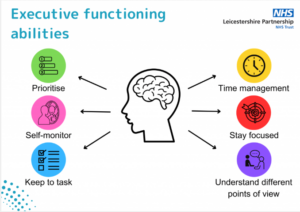

Executive Function

Executive functioning refers to a set of cognitive processes that enable us to plan, organise, problem-solve, remember information, follow instructions, regulate emotions, and stay focused despite distractions. Sometimes called the brain’s “air traffic control system,” it plays a key role in reasoning, multitasking, and self-regulation.

For neurodivergent individuals, the development of executive functioning is often delayed, and difficulties may persist throughout life. These challenges typically originate in the frontal lobe and are especially affected by three core areas:

-

Working memory

-

Inhibition (self-control)

-

Flexible thinking

These core skills influence other aspects of executive functioning and impact daily life in ways often overlooked. Tasks that may seem routine can be significantly more difficult or exhausting for individuals with underdeveloped executive functioning.

Key messages:

-

As educators we must remember that children (and adults) will all come to us with different brains and different ways of understanding and experiencing the world. This is a completely normal and wonderful part of humanity and should be embraced. It is not out job to try to make all children fit the same mould, but rather to adapt to suit each child’s individual way of thinking.

-

It is important to remember that as educators we are not qualified to diagnose neurodivergences, our role is to support, inspire and nurture all children, and meet any needs which children may be communicating through their behaviour patterns.

- Sensory processing differences are more commonly associated with neurodivergent conditions, although a diagnosis is not necessary to experience these challenges. We must ensure we focus on needs, not labels.

- Masking is when a child or adult learns that the way they are is not accepted by society, and so they hide or change their behaviours to become more like ‘typical’ children. They might subdue a ‘stimming’ behaviour, hide their emotions, copy and mirror others or force eye contact. Masking takes a huge amount of effort and can lead to children and adults having low self esteem, burnout and mental health problems.

Ways we can do this:

Early intervention and support is crucial in getting it right for every child in our settings, we can have a huge impact by looking at what is in our power to support right now. To ensure that we are doing everything we can to meet any need that any child has, and ensure that our records reflect the journey of the child and what we know about them. It is important to note that sometimes children may require requests for assistance from other professionals, but our support must not be dependent on these referrals or labels.

Many of children’s needs can be met by making thoughtful adaptations within our everyday, universal support approaches.

To be neurodiversity affirming, we shouldn’t wait until a child is identified as neurodivergent to implement inclusive practices. Instead, design your core routines and environment with neurodiverse learners in mind from the start.

This might mean reducing sensory and cognitive overwhelm, setting realistic and achievable expectations, and providing regular opportunities for movement throughout the day.

Rethink norms around eye contact—understand that it isn’t comfortable or necessary for all children. In ELC, offer invitations to engage rather than forcing participation. As children move into more structured school environments, there may be more non-negotiable tasks, but your approach still matters. For instance, allowing a child to finish their current activity before transitioning, using ‘now and next’ visuals, maintaining consistent routines, and giving clear preparation for upcoming changes.

Visual timetables support all children, not just those who are neurodivergent.

Creating quiet, calming spaces within the learning environment is also vital. These should always be available, allowing children to access them whenever they need a moment of regulation or downtime.

Be curious about what might be driving a particular behaviour—all behaviour is communication, there is always a reason behind it.

Avoid using shame and blame. This can harm a child’s sense of self-worth and increase feelings of isolation. positive relationships are key to supporting all children, but particularly neurodivgent children.

Above all, remember that our interactions with children have a powerful impact. A small moment—positive or negative—can shape how a child feels, learns, and connects. Strive to make those moments supportive, respectful, and inclusive.

Modelling Respectful and Positive Touch

Staff must always remain mindful that children have different comfort levels and responses to physical touch. Some children may actively seek out affection and physical closeness, while others may prefer to avoid it entirely—and both responses are completely valid.

Adults should prioritise giving children autonomy and choice when it comes to their own bodies. This means seeking consent wherever possible, using language such as, “Would you like a cuddle?” or “Is it okay if I sit here?” to model respectful interaction.

Physical touch should never be used to control or coerce a child. Actions like pulling a child by the hand, repositioning them without consent, or physically guiding their hands to complete a task can undermine their sense of agency and safety.

Instead, foster an environment where touch is always respectful, consensual, and in tune with each child’s individual needs and preferences.

Focused observations are valuable tools for self-evaluation, helping to identify areas for improvement. They also provide factual insights about your service or a child’s experience within the environment.

Once you have worked out the need that the child is communicating through their behaviours, it’s time to put in place some support strategies. Keep in mind that all children are different and what works for one child may not benefit another. Give sufficient time to embed a new strategy, it may not have an impact straight away. Use a Care Plan + to ensure that all practitioners are on the same page and are using the same approaches. Involve families so that similar strategies might be adopted at home.

What is it?

What is it? Neurotypical: A person whose brain follows ‘typical’ development in regards to language, learning.

Neurotypical: A person whose brain follows ‘typical’ development in regards to language, learning.