Now that the Discovering Mathematics module has come to an end it has allowed me time to reflect on everything that has been presented in each lecture. There has been a range of guest speakers come in and take time to share their experiences and their observations specific to their own professions or vocations. This has been hugely beneficial as it has really hit home the extent to which maths is used in the wider society outwith the education environment,This for many of us was our taste of maths in operation outwith our placement environment,

It has changed my whole mindset concerning why maths principals are resourceful and relevant to everyday life, It forced me to broaden my horizons the way I viewed maths and I could appreciate that there are lots more functions available within maths that we can make use of outwith the obvious old favourites. One last thing we were asked to do by our lecturer was to bring in a favourite childhood board game and prepare some notes on the maths involved within this game. I chose to challenge myself and use the knowledge from this module to form the basis of my notes.

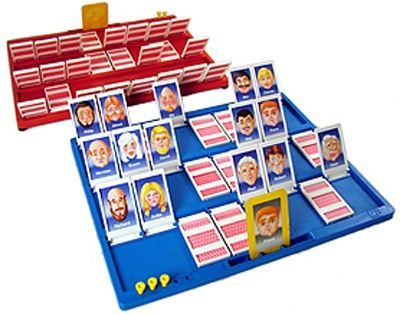

Ordinarily, I would have chosen something as simple as monopoly and chose the easy option of discussing the use of money involved. However, I decided to stick with my favourite childhood game and delve deeper with regards to the underlining fundamental mathematical principals involved, thus being ‘Guess Who’.

Aim of guess who is:

Each player starts the game with a board that includes cartoon images of 24 people and their first names with all the images standing up. Each player selects a card of their choice from a separate pile of cards containing the same 24 images. The object of the game is to be the first to determine which card one’s opponent has selected. Players alternate asking various yes or no questions to eliminate candidates, such as “Does this person wear glasses?” The player will then eliminate candidates by flipping those images down until all but one is left. Well-crafted questions allow players to eliminate one or more possible cards

The mathematical principals what I identified were:

- Data and analysis

- Probability and chance

- Process of elimination

Picking a game with no physical numbers involved was always going to be a challenge to pinpoint mathematical principals which apply. However, just by using the knowledge that I have gained through this module it has become apparent that maths goes so much deeper than numbers and figures. The principals above all relate to basic maths concepts that at school you learn alongside the use of numbers but by having the conceptual knowledge of using these fundamental maths procedures I can then apply them to different contexts in this case individuals on the board games features. This shows the power that mathematics can hold beyond the classroom if the correct pedagogy style is carried out. Which relates to Lipping Ma’s work that PUFM is essential in carrying out ‘teaching excellence’ which will provide learners with the ‘how and why’ of maths. Being able to solve a maths problem is not always the important task in hand within the classroom, learners will benefit much more if they can explain how they got to the answer and having the conceptual knowledge of why you are adopting that strategy to solve the problem in the first place. This will understandably cement a value towards the maths being taught and learnt in schools and children will be able to take this knowledge of fundamental mathematics into their adult life and more importantly be aware of when they need to utilise it in different contexts.

Lipping, M (1999). Knowing and teaching elementary mathematics: teachers’ understanding of fundamental mathematics in China and the United States. New York and London: Routledge.