24.School absenteeism and educational attainment- Evidencefrom the Scottish Longitudinal Study- Klein et al School Absenteeism and Educational Attainment–

Evidence from the Scottish Longitudinal Study, May 2022- Authors: Markus Klein, Edward Sosu, Esme Lillywhite

Forth Valley and West Lothian Regional Improvement Collaborative

Attendance Focus: August -October 2022

Research Summary

| Research reference (with link) |

| School Absenteeism and Educational Attainment- Evidence from the Scottish Longitudinal Study, May 2022– Authors: Markus Klein, Edward Sosu, Esme Lillywhite |

| Research methodology / Data Collection methods |

| The data used in this study comes from the Scottish Longitudinal Study (SLS), a large-scale, anonymised record study linking various administrative and statistical data in Scotland. Using semi –random birthdates, the study covers 5.3% of the Scottish population. The researchers also included 2001 census data linked to administrative school records and Scottish Qualification Authority (SQA) data from 2007 to 2010. The administrative school records included reasons for absence, while the SQA data provided records of exam grades. The census data allowed the researchers to adjust their analyses for key household socioeconomic information and background characteristics. They took into consideration two student cohorts who were in their last year of compulsory schooling (S4) in 2007 and 2008 respectively and who were followed into the final year of post-compulsory schooling (S6) in 2009 and 2010. |

| Key relevant findings |

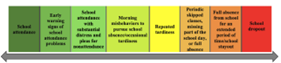

| The study sought to ascertain if absenteeism had an overall link to attainment in national examinations taken at the end of compulsory schooling (S4) and post- compulsory schooling S5/S6 and also to examine whether the link between absenteeism and attainment varies with the reason for absence (truancy, sickness absence, exceptional domestic circumstances, and family holidays).

When the researchers focused on S4 they discovered that overall absences negatively impacted on educational attainment. ‘A one percentage point increase in days absent was associated with a decrease of 3% of a standard deviation in tariff scores*.’ That essentially is a 3% decrease in educational attainment. They also discovered different types of absence were linked with attainment. For example- Sickness or Truancy Absence- A 1% point increase translated into a 4% standard deviation in academic achievement Family Holidays—A 1% point increase translated into a 3% standard deviation in academic achievement Exceptional domestic circumstances- were associated with a drop of 2% standard deviation in academic achievement When looking at S5/6 the researchers found again that overall absences had a negative influence on academic achievement. In summary the researchers found- 1. School absences are detrimental to educational attainment in national exams at the end of compulsory (S4) and post-compulsory schooling (S5/S6) in Scotland. 2. Truancy, sickness-related absences, and absences due to exceptional domestic circumstances each have a unique negative impact on educational attainment at both stages. 3. The findings suggest three additional pathways through which absence may affect academic achievement: a behavioural pathway, a health pathway, and a psychosocial pathway. 4. The research challenges previous assumptions that unexcused absences are more harmful than excused absences and calls for equal emphasis on tackling all forms of school absence. Research and interventions need to focus on mitigating the harmful consequences of school absenteeism, considering the reason for absence. |

| Questions research raises |

| How will you ensure that all staff have an understanding that any absence, excused or unexcused, has an impact on attainment?

How will your establishment use your data on types of absence to provide a considered approach when adopting interventions that are fit for purpose? |

| Follow up reading suggestions |

| Eaton, D. K., Brener, N., & Kann, L. K. (2008). Associations of health risk behaviors with school absenteeism. Does having permission for the absence make a difference? Journal of School Health, 78(4), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00290.x

Klein, M., Sosu, E. M., & Dare, S. (2022). School Absenteeism and Academic Achievement: Does the Reason for Absence Matter? AERA Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211071115 |

* We measured absenteeism by the proportion of days a pupil was absent from school during S4 and S5. The possible reasons for absence were truancy, sickness absence, exceptional domestic circumstances, and family holidays. Educational attainment was measured using grades from the national exams given at the end of S4 and S5/S6. We then converted information on number of subjects taken, level of difficulty, and grades into an extended version of the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) tariff points score (for more details, see section 3.3 in Scottish Government, 2012).

Tier 1

Tier 1