Forth Valley and West Lothian Regional Improvement Collaborative

Attendance Focus: August -October 2022

Research Summary

| Research reference (with link) |

| A Multi-dimensional, Multi-tiered System of Supports Model to Promote School Attendance and Address School Absenteeism. (Kearney & Graczyk, 2020) |

| Research methodology / Data Collection methods |

| The paper discusses how the MTSS (Multi-tiered System of Supports) pyramid model is a practical and effective model to support the implementation and integration of nuanced interventions and systems to improve school attendance and ameliorate absenteeism. Domain clusters are ways to categorise school attendance problems using themes that frequent the literature. The report details different ways that a multi-dimensional MTSS model could be applied to each of the domain clusters, giving referenced research-backed examples of intervention strategies within each domain and across each tier. |

| Key relevant findings |

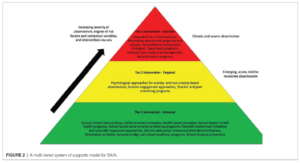

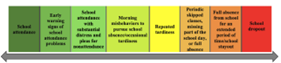

Tier 1 of the MTSS model largely focuses on universal, school-wide practices and primary prevention strategies to promote adaptive behaviour (e.g. successful academic achievement, social-emotional competencies, engaged classroom behaviour) and to deter maladaptive behaviour that can lead to school absenteeism. Generally, Tier 1 interventions include those designed to improve school climate, physical and mental health, social and emotional competencies, parental involvement, academic readiness and cultural responsiveness. As part of Tier1, the report recommends universal data screening to assess and predict school attendance problems (standardized test results, discipline referrals, behaviour questionnaires). The paper recommends using the model below, a spectrum of school attendance problems, to identify the severity of absenteeism. The report also advocates early warning systems to prevent school absence problems. Tier 1 of the MTSS model largely focuses on universal, school-wide practices and primary prevention strategies to promote adaptive behaviour (e.g. successful academic achievement, social-emotional competencies, engaged classroom behaviour) and to deter maladaptive behaviour that can lead to school absenteeism. Generally, Tier 1 interventions include those designed to improve school climate, physical and mental health, social and emotional competencies, parental involvement, academic readiness and cultural responsiveness. As part of Tier1, the report recommends universal data screening to assess and predict school attendance problems (standardized test results, discipline referrals, behaviour questionnaires). The paper recommends using the model below, a spectrum of school attendance problems, to identify the severity of absenteeism. The report also advocates early warning systems to prevent school absence problems.

Tier 2 interventions are designed to target emerging individual cases of school absenteeism, or those of mild/moderate absence severity. These include interventions designs to improve family functioning, including psychological therapy approaches linked to emotional distress, student engagement approaches and teacher/peer/other person-based mentoring programmes.

Tier 3 interventions include those designed to address individual cases of chronic and severe absence, through a multi-agency approach. Such interventions include expanded Tier 2 therapies, alternative education programmes and family involvement strategies. Kearney et al. recommend the introduction of a Tier 4 to include very intensive interventions for youth with psychopathology, which may involve a blend between education and inpatient/residential facilities.

Domain cluster 1 – The paper defines and explains different types of absenteeism; School refusal – reluctance to attend due to emotional distress, child-initiated Truancy – related to behaviour, illegal absenteeism, child-initiated School withdrawal – parent-initiated, often withdrawn for economic/caregiving purposes School exclusion – disciplinary reasons, school-initiated Common interventions mainly include cognitive-behavioural-oriented practices, which address internalising and externalising behaviour problems, and family interventions such as parenting skills training and family therapy.

Domain cluster 2 – functional profiles and analysis (what are the motivating factors of a child’s absenteeism?) As outlined in the report, a common functional profile is based on the motivating conditions of child’s absenteeism. An example of this was developed by Kearney et al. who referred to the following aspects;

The report recommends that these factors should be considered at each tier to adopt preventative, targeted and nuanced interventions and provides research-backed examples of these.

Other domain cluster options: Domain cluster 3 – preschool, elementary, middle and high school Domain cluster 4 – ecological levels of impact on school attendance and its problems Domain cluster 5 – low/ moderate/ high absenteeism severity |

| Questions research raises |

| Could we use the structure of the MTSS model to highlight effective interventions across each tier, supporting schools to adopt appropriate interventions based on the severity/nature of absence cases?

Do we value universal interventions enough as a preventative measure to avoid or reduce the risk of school attendance problems arising? |

| Follow up reading suggestions |

| Kearney, C. A. (2016). Managing school absenteeism at multiple tiers: An evidence-based and practical guide for professionals. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kearney, C. A. (2018). Helping school refusing children and their parents: A guide for school-based professionals (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

|