How often do you take a chance? The answer would be every day. Every day we take a chance, whether it be crossing the road, going to the gym or simply choosing to watch the TV. We cannot predict the potential outcome of doing something, yet, without even thinking, we create the factors that are influenced by our decisions. Something of which has lead us to be where we are to this day.

Before this module began, I remembered learning about probability in high school. I was never intrigued by the prospect of learning about probability. However, after the lecture about this I have felt that I can relate chance and probability to my personal experiences and highlight to pupils the basic maths behind this, whilst making it enjoyable to learn about. Inter-connectedness is a concept of Liping MA’s that can be used between maths and our everyday lives (Ma 2010). By interconnecting our experiences with the subject of probability, basic mathematical skills can be integrated into our everyday experiences, something which I believe is important when obtain fundamental maths skills.

Probability is “the likelihood or chance that something may happen” (Turner, n.d. p5) and can be worked out by:

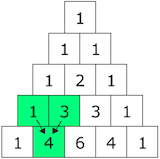

Probability of something happening = The number of ways it can happen – over – the total number of outcomes

For example, when rolling a dice there are 6 possible outcomes. However, if I were to only try and role a 5, the possibility of this would be 1 in 6. In many cases people try to predict the possible outcome, however as we have discovered in maths, it is not as simple as this.

Gambling has a profound and direct link to probability and chance. By taking this chance it can be the profit or the lost to some people’s bank balances. Those who are serious gamblers are costing the government £1.2 billion a year (IPPR, 2016). This is not only impacting the economy but can also cause extreme debt for some people, and a break down in relationships and mental health. This is why some people try to predict casino games and influence the outcome, in the hope they can solve the problem (Aasved, 2004).

There are aspects of gambling which are linked to multiple perspectives. This is about having a variety of different ways to reach an answer. For example, there are variety of meals you can have in a restaurant. Say for example there were 2 choices for a starter, 3 for main meal and 3 for dessert, you have to list of different meals that you can possibly have. Therefore, there are many different combinations and to figure this out multiple perspective is important.

Gambling is something which relies on randomness and probability (Turner, n.d). When discussing this in our lecture, we all thought that surely humans can create randomness effectively? Wrong! We wrote our predictions of either heads or tails, if we were to flip our coin 30 times. I thought I would try and mix it up a bit, put heads 4 times in a row, a couple tails etc, but the answers truly baffled me. It ended up being completely 50/50. Even when I was trying to be as random as possible. The results were similar on a larger scale of our class, with the majority of people being one or two off the other. When actually flipping a coin, my results were 21 heads and 9 tails, and this varied around the lecture room. Therefore, as humans, we THINK we are being random, however nothing is quite that simple and we actually try to create logic results rather than random. I remember when conducting my answers, I thought I had to put a head and not another tails because 4 tails in a row was being silly, yet the physical experiment proved this to happen with heads.

Using a coin is a simple way of introducing probability and chance to children, as there are only two outcomes. If they have the basic skills and understanding of what a half or 50% means then probability can quickly follow behind. This aids their longitudinal development, as they have the basic skills prior to probability and therefore they can build on this to have a deepened understanding of problem solving and the possibilities of finding the answer. It also helps them in more complex scenarios, for in class work and future work, if they were working in a restaurant for example. Therefore, multiple perspective, basic skills and longitudinal coherence, all key skills in profound fundamental maths (Ma, 2010) can be shadowed through everyday maths.

It is important that we recognise that gambling can possibly be predicted. However, slot machines and casinos profit more from us than we would ever earn back (unless you’re the 1 in 45057474 to win big on the lottery! (Lottoland, 2016)). Slot machines are to us, a quick and easy way to win money back. Charles Fey, developed the Liberty Bell machine in 1895, which has 3 reels and 5 symbols. This machine in particular pays out 50% of the time with an average of 75% pay-back. Therefore, although you seem to ‘win’ more, you are in fact, losing more!

Stefan Mandel, 1964, applied to buy every combination to the Romanian lottery. He followed this up by doing this with the Virginia state lottery. The video below highlights the result of this.

In conclusion, probability and chance is something that we use every day. Some people take this for granted and some take it to extremes. However, we have the ability to use multiple perspectives to figure out possible outcomes, which can be used in our daily lives and in maths in primary school. Yet, probability on a gambling scale, as seen in the video, can be on a completely different scale to our everyday probability. I believe that Liping MA’s principles are important here and they are concepts that I will look at deleloping in future placements and my teaching career.

References:

Aasved, M. (2004) The Biology of Gambling. Springfiled: Charles C Thomas.

LottoLand. (2018). The Probability of Winning the Lottery. Available: https://www.lottoland.co.uk/magazine/the-probability-of-winning-the-lottery-.html. (Accessed on: 17th October 2018)

Ma, L. (2010) Knowing and Teaching Elementary Mathematics (Anniversary Ed.) New York: Routledge.

Slot Machine History (2010). Who is Charles Fey? Available: http://slotmachineshistory.com/charles-fey.htm. (Assessed on: 15th October 2018)

The Progressive Policy Think Tank. (2016). Cards on the table: The Cost to Government Associated with People Who Are Problem Gamblers in Britain. Available: https://www.ippr.org/publications/cards-on-the-table. (Accessed on: 16th October 2018)

Tuner, N. (no date) Probability, Random Events, and the Mathematics of Gambling

Wherbert, P. (2010). Stefan Mandel (online video) Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TqFp0efLK0 (Accessed on: 16th October 2018)