We are now at the end of this module and I honestly am humbled with the insight into technology that I never thought possible. I have appreciated the time we got to spend together and three insights have came to light for me:

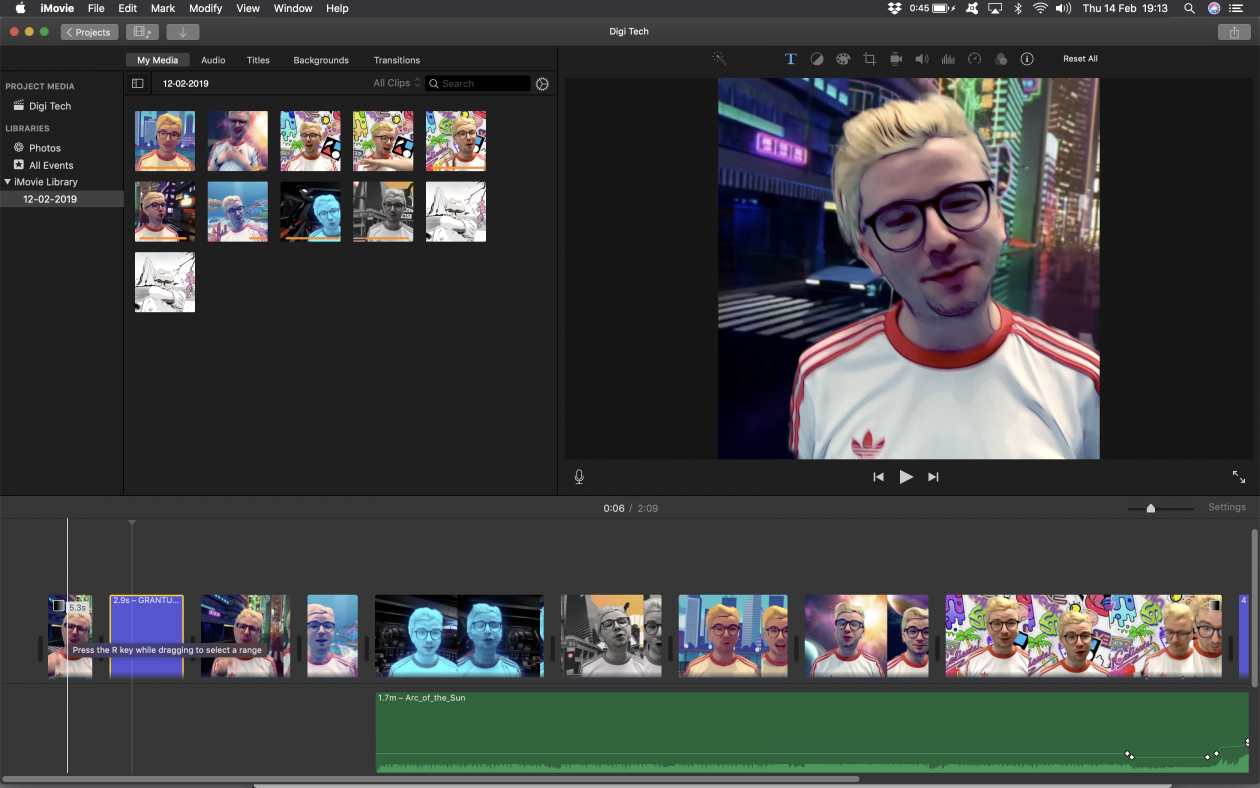

- Technology is and should be part of the modern classroom.

- It can and should be more than a reward for doing well at traditional learning.

- I am privileged in the knowledge I have in technology and want to aid anyone that feels inadequate feel confident using technology in their classroom.

The Scottish Government agrees and has a whole manifesto dedicated to the teaching and learning of technology in education (Education Scotland, 2017). It has been used as my foundation of not only what I’ll do for assessment tasks, but why and how I planned to create these learning experiences specifically. My confidence in using technology was definitely an advantage but doing this module allowed me to reinforce the knowledge I had but allow deeper understanding of how technology can impact a classroom of learners.

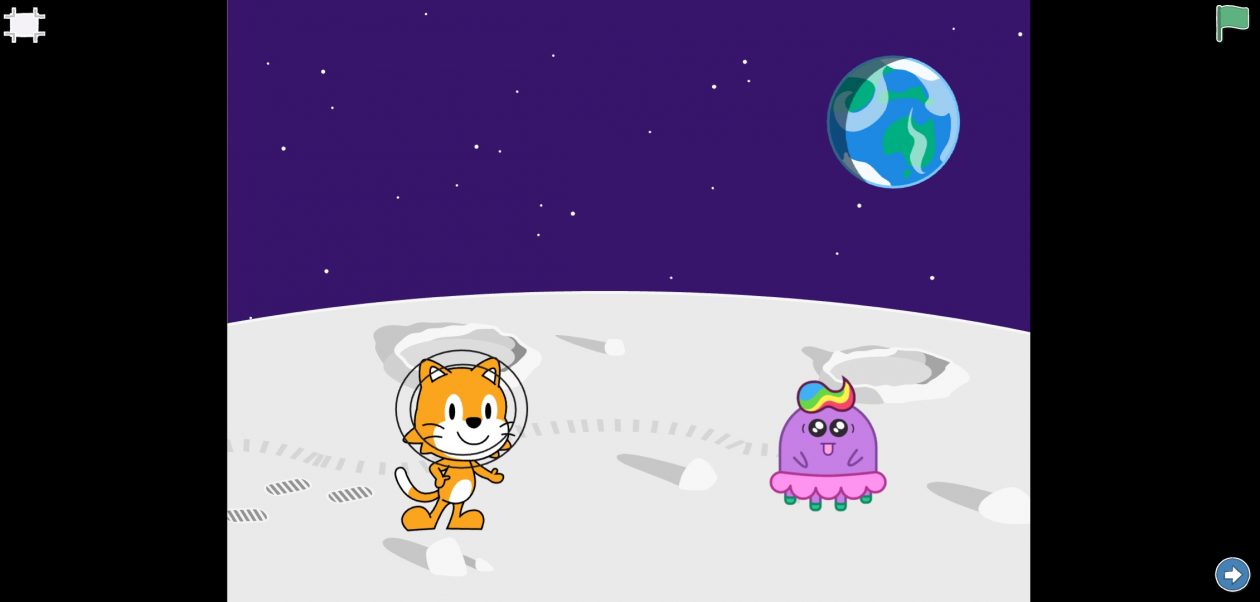

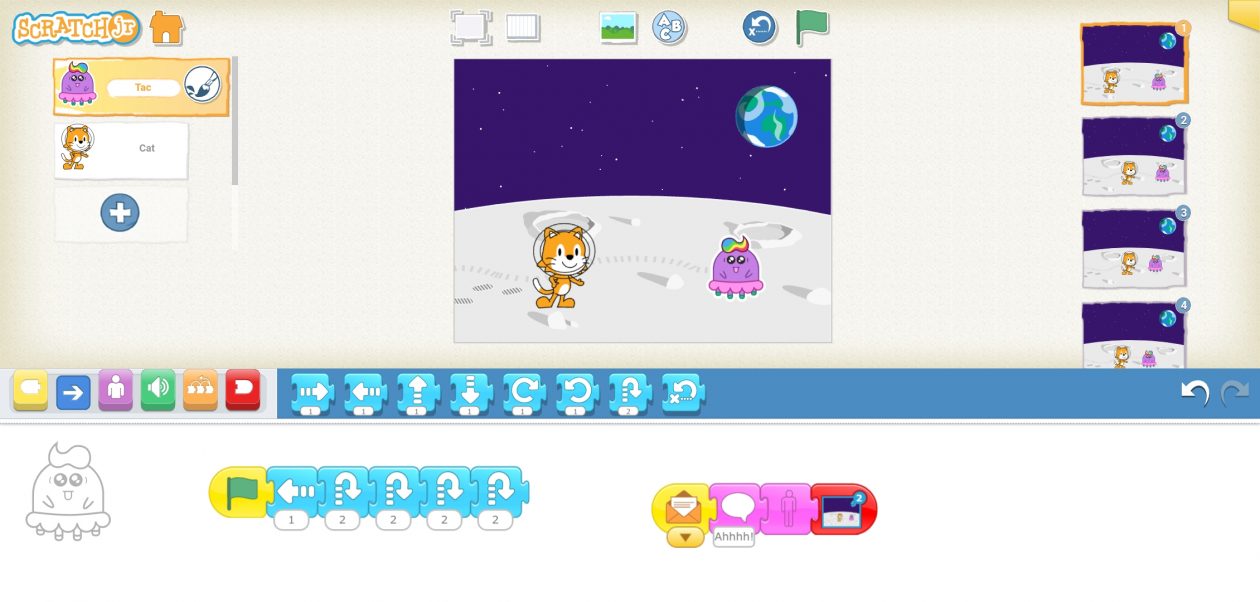

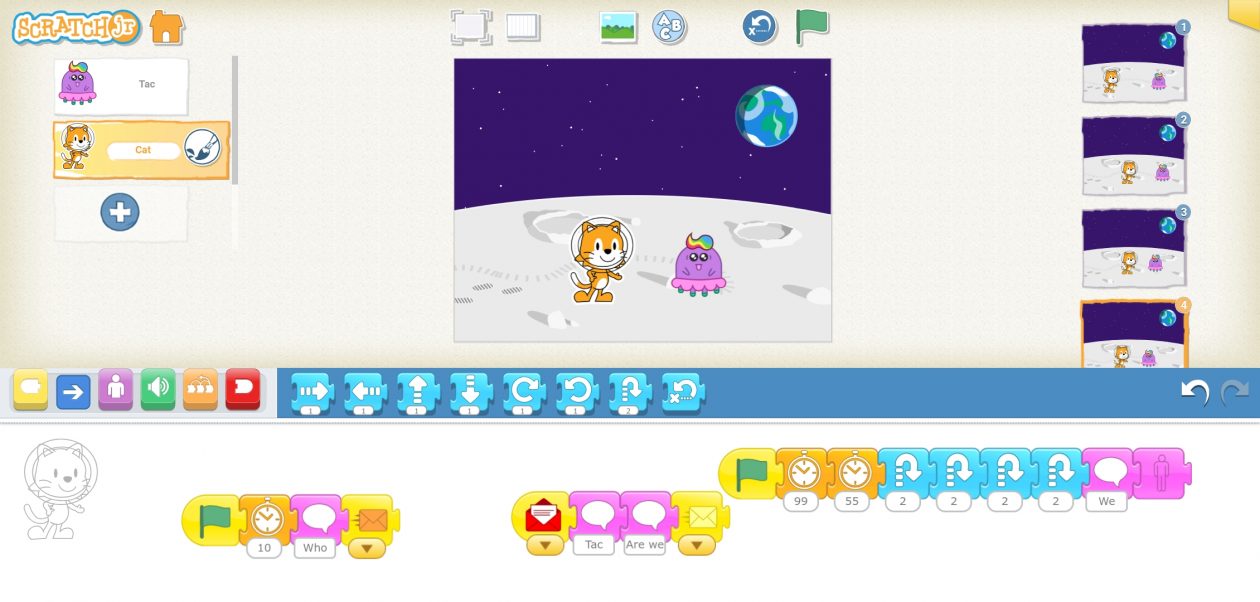

The main thing that I will still have to work on is that – only from experiences in my schooling days where there was one computer in the entire school – technology is not a reward but in fact another means of providing meaningful lessons to a generation of “Digital Natives” (Prensky, 2001). Although the lessons we created were fun this was a byproduct and not the main goal – although if learners are having fun Beauchamp (2012) would agree this creates the opportunity for deeper understanding in the subject. Ultimately – as teachers – we should be aiming for a classroom of successful learners, confident individuals, responsible citizens and effective contributors and I agree with Beauchamp (2012) that technology is an effective gateway to achieve this.

It has always been in my nature to help those who are struggling in their learning and plan to keep this trait for the rest of my life. I noticed throughout the module that I did have a higher base knowledge – and love – of technology in comparison to those I worked with on collaborative projects. When working in collaboration with those who struggled with technology it allowed me a chance to reflect and think forward about having learners that may – like those I worked with – be disengaged from technology but teaching them to persevere and understand that as a tool can be a unique way to gain the same learning that may be done traditionally (Beauchamp, 2012).

As Shakespeare would say “Parting is such sweet sorrow, That I shall say good night till it be morrow.” I hope that with this blog I’ve shown that the use of technology in the classroom will be a huge facet of my style of pedagogy and that I wish to inspire the next generation of learners to be problem solvers for whatever they may face.

References:

Beauchamp, G. (2012) ICT in the Primary School: From Pedagogy to Practice. Pearson.

Prensky, M. (2001) Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. MCB University Press.

Scottish Government (2016) Enhancing Learning And Teaching Through The Use Of Digital Technology: A Digital Learning And Teaching Strategy For Scotland. Scottish Government [Online] Available at: https://www2.gov.scot/Resource/0050/00505855.pdf