If you have any accessibility requirements or would like to request the course content in a different format please contact amy.johnson@educationscotland.gov.scot and hannah.brown@educationscotland.gov.scot

Gender and Interactions

In this module we will build on what was covered in Module 1 and explore:

- Patterns in whole class interactions and learner participation

- How these patterns of interactions can lead to differing levels of self-confidence

Practitioners are in a unique position to mitigate the effect of this through:

- Observing and reflecting on existing patterns of interactions

- Embedding strategies for equitable interactions

Whole class and small group interactions; recognising the patterns

Note that the term ‘whole class’ here, is used to refer to whole group interactions in ELC settings as well as in classrooms.

Introduction

- Our interactions with and expectations of children and young people are influenced by gender roles and unconscious bias. For example, we may use gendered pet names. Errands are often gendered, with girls doing more of the domestic or tidying errands, and boys perhaps being more often asked to lift heavier objects. Our expectations of behaviour may vary based on gender. For example, sometimes the expectation might be that boys are more likely to exhibit poorer behaviour and as a result are disciplined more harshly; conversely, that expectation of worse behaviour from boys might result in that behaviour being accepted/excused, whereas girls exhibiting the same behaviour might be reprimanded.

- The way interactions are initiated during a whole class or group activity can impact an individual’s willingness to contribute. This in turn will impact their confidence in their abilities, how engaged they are in the subject and ultimately their attainment. Our interactions with learners can reinforce or dispel stereotypical patterns of behaviour. (Howe, 1997)

- Research suggests that boys tend to experience a higher number of interactions with their practitioners, and girls a lower number, than would have been expected from their proportionate distributions in the classes. (Drudy & Chatháin, 2010)

- In whole-class interactions, boys tend to initiate more public interactions than girls. Girls are more likely to seek shorter, more private interactions with practitioners. Boys also tend to talk more overall to practitioners than girls tend to. Children who initiate interactions are also more likely to experience more interactions. (R & R, 2009)

- Research suggests that most practitioners believe that they give equal time to girls and to boys, particularly in support of their learning. However, focus group interviews with students and classroom observations suggest that this is rarely achieved in practice. In most schools, boys appear to dominate public classroom interactions, while girls participate more in practitioner-learner interactions. These differences are learned not innate. The patterns are likely to start to emerge early and become reinforced over time. (Younger, Warrington & Williams, 2010)

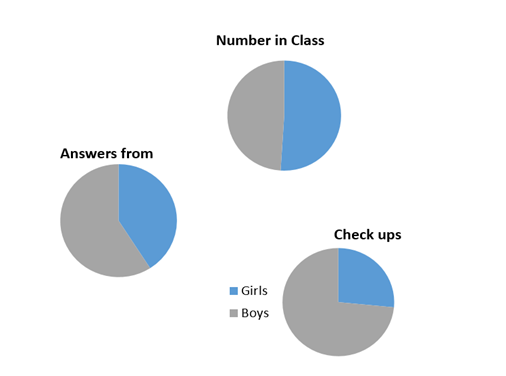

- The pie charts below show data from the Improving Gender Balance Scotland pilot. When working with settings we see these patterns in our observations repeatedly (although not universally), however the data presented here was collected from twelve classes ranging from S1 – S6. The results presented here are the averages across all twelve classes and show that despite there being marginally more girls on average in the classes, the girls were less likely to answer questions, and even less likely to be checked up on by the practitioner.

- These interactions in the classroom, i.e. the more public learning process of boys and the more private and individualised interactions for girls, may create learned behaviours. For example, the consistently more private interactions adopted by many girls may not help them develop confidence in engaging publicly in general. There are suggestions these patterns impact confidence around speaking up in professional contexts in the future such as public speaking or presenting in meetings. (OECD, 2015).

- As discussed, boys and girls often interact in different ways and for different reasons. Whole-class interactions can be dominated by a sub-group of learners (for example, a sub-group of the boys in the class), often because they are making themselves more visible. There are various strategies and techniques that can be employed to support learner understanding of what balanced participation looks and feels like.

- When strategies to promote more equal participation such as Assessment is for Learning are used consistently this can have a positive impact on all learners and the interactions they have, developing confidence to contribute in class and increasing confidence. (OECD, 2008)

- High quality questioning and thoughtful scaffolding of answers can support more balanced interactions and increased understanding across a group of learners.

- Levels of learner participation in whole class interactions rely on a number of factors (Lemov & Robinson, 2017):

- The preparation by the practitioner of key questions (including anticipated responses)

- Whether or not the means of participation is clearly defined (Assessment is For Learning, hands up, shout out, lollipop sticks etc…)

- Whether time is given to learners to allow responses to be prepared (written or verbal)

- The expectations around how learners respond (is saying “I don’t know” acceptable or is scaffolding used?)

- How practitioners react to learner responses (i.e. are responses accepted directly or are they scaffolded and unpacked?)

- Both within group or class teaching, it is important to ensure all learners are aware of the expected process for giving responses and that these are reinforced.

- Evidence from Making Thinking Visible approaches suggests that mapping out an interactions route in your setting to follow each day can support more equal interactions across learners. Seating plans should be used to support learning and teaching and equitable interactions whenever possible.

- The below is an excerpt from ‘The Problem in Teaching and How to Address It’, 2019 by Tom Sherrington. It suggests approaches that can be used to support engagement from all learners. – case studies

“Weak questioning or response techniques

Echoing the issues with testing procedures, weak questioning allows lessons to be driven exclusively by the students who know, rather than the students who don’t. I’ve seen many many lessons where 2 or 3 students answer all the questions, and the teacher has used their responses as the gauge for the level of understanding in the room. ‘Hands up’ or ‘call out’ questioning is widespread as the default mode of questioning. It is possible to sit in far too many lessons as a low-confidence or shy learner and never be asked to contribute, never be asked to explore your ideas or understanding – because other, more confident students chip in and dominate and this is just how things are all the time. I feel quite strongly that this kind of practice really has to change.

Solution

- View the purpose of questioning as providing feedback to you: have I explained this well? Do we have enough understanding across the class to justify moving on? Sample enough students to get a reasonable picture.

- Use a good repertoire of questioning! Great Teaching: The Power of Questioning

- Cold Call and Pair-Share should be absolutely routine. I really feel that if more pair discussion, tightly focused and time managed, was built into lessons, involving all students, a lot more practice would be happening and more misconceptions and difficulties would emerge. If you listen in discreetly as all students air their ideas – it gives a powerful insight. There is great power in giving students space to rehearse their thinking; to hear their own thoughts.”

This section contains some prompts for reflecting on the themes above. You might like to consider, for your context:

- What kind of interactions are learners initiating? (Public, personal, academic, comments on other learners etc…)

- Are there patterns of who tends to respond, and who tends not to?

- What learned behaviours might be influencing why certain individuals or groups dominate interactions?

- What learned behaviours might be influencing why certain individuals or groups tend not to contribute publicly?

- Do learners have feedback on the dynamics of group interactions? What do learners feel would support more balanced interactions?

- How is a shared understanding of what ‘balanced participation’ might look like achieved within your setting

- What strategies from Assessment is For Learning or Making Thinking Visible might be useful to promote equitable interactions in your setting?

Please try something out in your classroom/setting. The questions/ideas below are prompts but are not exhaustive or prescriptive. You might want to spend time observing patterns, reflecting on practice, trying a new approach etc. Please use your reflective journal to record your thinking.

- Observe patterns of interactions in small teaching groups/whole class.

- Reflect on the types of interaction you find yourself initiating in your setting, do you think these encourage some groups to engage more than others?

- What kind of interactions are children and young people initiating? Are there gender differences?

- Could you try out a new AiFL strategy? Here are some possible AiFL strategies.

- Pre-develop questions to use in whole class or group teaching experiences.

Recording What You Did

- What did you observe?

- What did you try?

- What worked well?

- What were the challenges?

We would love to hear what you’ve observed/tried this module. You can contact us any time. We will try to reply quickly, but will ensure we set aside time to respond during the feedback week to discuss. Please use the email address given to you at the introductory day.

Collaboration Week:

Please also make time to share your reflections/activities with the rest of the group & read what they’ve been up to. Click on the relevant link below