This page contains a brief summary of these two concepts. Fife employees can access a self-led Professional Learning Module on the Fife Intranet.

Critical Pedagogy is an important framework and tool for teaching and learning because it:

- recognizes systems and patterns of oppression within society at-large and education more specifically, and in doing so, decreases oppression and increases freedom

- empowers students through enabling them to recognize the ways in which “dominant power operates in numerous and often hidden ways

- offers a critique of education that acknowledges its political nature while spotlighting the fact that it is not neutral

- encourages students and instructors to challenge commonly accepted assumptions that reveal hidden power structures, inequities, and injustices

From Harvard Research Guide: Critical Pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is based on Critical Theory. Critical theory is any approach to humanities and social philosophy that focuses on society and culture to attempt to reveal, critique and challenge power structures.

In its modern interpretation, Critical Pedagogy developed from the work of Paolo Freire and Henry Giroux. It is the belief that the core purpose of education is to empower learners to be critical thinkers. Critical thinkers are more likely to connect their own problems and experiences to the wider social contexts around them. Freire calls this ‘critical consciousness‘ and makes it a core aim of education. In line with the GTCS professional standards, teaching is held to be an act of environmental, economic and social justice, therefore these issues cannot be separated from the curriculum.

In age and stage appropriate contexts, critical pedagogy will often explore

- Power structures

- Patterns of inequality

- Oppressive acts and systems

- Social movements

- Political acts

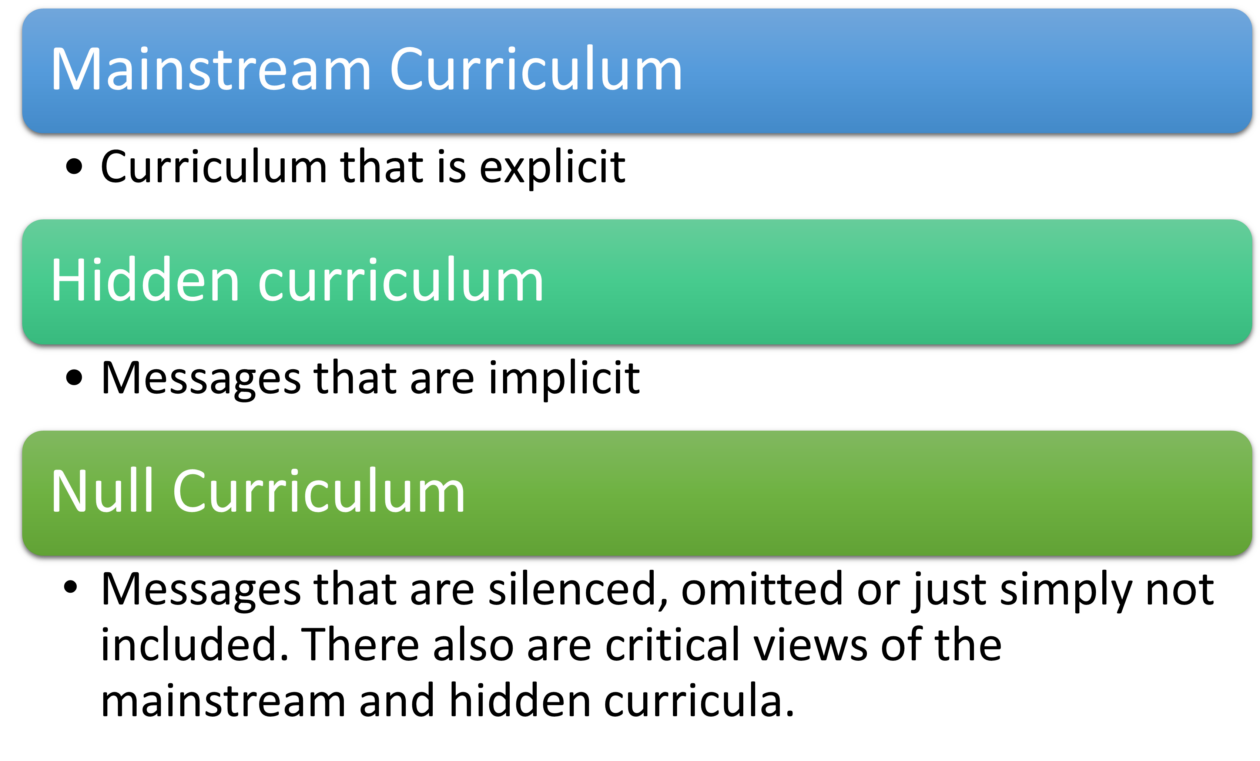

This can be as simple as identifying an issue with litter in the school playground and acting to address it through awareness campaigns and fundraising for bins etc. However, it could also be identifying examples of injustice in local, national or global society and getting involved with campaigns to address this. Thinking about the three types of curricula can help with this (hover for an example):

Mainstream Curriculum

Columbus was a strong, brave "explorer" who opened the doors for European colonisation of the Americas.

Null Curriculum

Columbus violently exploited and dominated the indigenous peoples of the Americas, which was part of a larger European mindset that allowed for genocide, enslavement, assimilation, colonisation and, in contemporary settings, globalisation (or global Westernisation).

Hidden Curriculum

Europeans are more advanced and sophisticated than the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Themes of Eurocentrism, Patriarchy and Technology over Nature.

Find out more in a brief introduction here or from the links below.

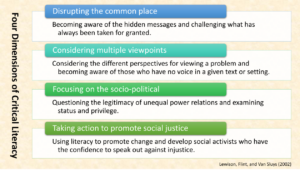

Critical Literacy

A key skill in developing critical thinking is Critical Literacy. This is a lens, frame or perspective for engaging with texts, for teaching & learning, and for curriculum design.

When we take a critical literacy stance, we recognise that all forms of communication, including texts (writing, video or audio) “are social and political acts that can be used to influence people and lead to social change” (Comber and Simpson, 2001).

We tend to think of critical literacy as something academic, perhaps associated with university study. However this is only one form of critical literacy. Even in nursery or primary school, the stories, songs and games we choose to use (or choose not to use) are never neutral. They are written and read from specific perspectives, as we read we draw on our past experiences and interactions with the world to help us understand. A similar process occurs when we write.

As educators we need to, and also teach our children and young people to, “read evaluatively and analytically to deconstruct the shape texts take, the choices text designers make in constructing texts, as well as the social impact of those texts (and the world views they represent), to reveal:

- how they serve the interests of some and not others

- how they include, exclude or silence particular voices

- how they (mis)represent ideas, identities, communities

- how these texts, and ways of representing, might be redesigned in socially just ways.”