Teaching and Learning

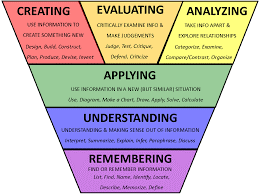

Since I arrived at Dundee my understanding and appreciation of the difference between instrumental and relational learning has increased exponentially. In reading the ideas from Colley et al. (2002) I feel glad to see them advocating learning as a social and relational process. Having recently attended the Scottish Mathematical Council’s (SMC) Stirling Maths Conference, I was completely blown away by an unexpected lightbulb moment that made me stop and question everything I have ever done in a classroom. It was particularly to do with teachers teaching skills, knowledge and understanding at the bottom end of Blooms’ Taxonomy in class time followed by students going home and doing homework on higher order skills, such as applying, analysing, creating and evaluating. Why, as creative, experienced, intelligent professionals are we using our precious time with our young people to teach them skills that the majority of them could pick up themselves with a basic introduction? Why are we not using our time to build on this ‘basic’ knowledge and how to apply, analyse, evaluate, experiment with and create new learning from it? What a waste of time!

http://blog.curriculet.com/wp-content/uploads/Blooms-Taxonomy.png

I do realise that it is unwise to view things in such simplistic terms using Blooms’ Taxonomy but considering Blooms’ Taxonomy was the catalyst for realising that I have been doing the monotonous, easy transferring of knowledge from me to my pupils rather than using my skills to help them be co-constructors of their own learning in order that they take and make sense of and add relevance to THEIR own situation. What a waste of MY talent! Although I have instinctively been teaching in a relational way (Skemp, 1972), I need to help my pupils identify how one aspect of their learning relates to another and that actually teaching in this way IS better than teaching the rule for doing this and the procedure for doing that.

As Colley et al. also suggest, learning is a social process. One of the most underused strategies for teaching mathematics is talking about it. If you walk into a school, primary or secondary, you are still more often than not likely to find children doing mathematics in silence; they are usually sitting in groups but working individually in silence. This is changing in primary classrooms, particularly in early years classes, but in secondary schools the overwhelming need to meet assessment targets in terms of ‘getting through the course’ drives the way that mathematics is taught; this is not a criticism merely a statement of the reality of the situation and no judgement is assigned to this. There are, however, some practices being trialled in some secondary mathematics departments, such as the flipped classroom, which may help to meet both the need to get through the material whilst using the face-to-face pupil-teacher interaction in a more productive way.

How can we support our students in engaging in a deeper approach to their learning?

In reflecting on myself as a learner, I have always been someone who has done what was needed to be done and therefore I would consider myself to be a strategic learner. I learn deeply the things that will be of practical use in my job, are relevant to me and my way of working and that help me to do my job more effectively. I have consequently engaged with learning more deeply since I have identified a clear purpose for learning.

To answer this question in general terms the Curriculum for Excellence (CfE)(Education Scotland, no date, no page) does a good job in this regard. Education Scotland (no date) encourage educators to consider the 7 principles of curriculum design to engage our learners in deep learning.

- Breadth

- Depth

- Coherence

- Relevance

- Progression

- Challenge and enjoyment

- Personalisation and choice

From these 7 principles, what I have identified as my motivations for learning more deeply are: relevance, coherence, personalisation and choice, challenge and enjoyment and progression, in that order.

In working with the PGDE students on co-operative learning, one of the key things I have been trying to relay is that the children have to be involved in their own learning, it has to be purposeful and that the teacher’s job is as a facilitator of the learning rather than the architect of it. Shuell (1986) in Biggs and Tang (2007) illustrates what I have been saying:

It is helpful to remember that what the student does is actually more important in determining what is learned than what the teacher does.

It occurs to me that perhaps the biggest change in my attitude towards teaching is tied up in my idea of my own importance. When I first started teaching I felt I was the most important person in the classroom. When I retrained as a primary teacher, my class and I were the most important people in the school. As a Depute Head Teacher everyone in the school was important including me and then as a Head Teacher everyone in the school was important, except me. So now, when I plan for an input, the first thing I think about is what do the students need to know about the topic closely followed by, how am I going to engage the students in this learning and what will make this happen. How very interesting – ego?!

In reading Teaching Learners to be Self-Directed http://longleaf.net/wp/articles-teaching/teaching-learners-text/ the above relates to initially me being the teacher of Stage 1 learners, not necessarily that they wanted to be Stage 1 learners but that I treated them in that way. Then I moved on to be a teacher of Stage 2 learners in that I tried to inspire and work with them. I would say that learning about co-operative learning strategies and gaining in experience and confidence has enabled me to move my learners towards becoming Stage 3 learners but I don’t know if I will ever be able to take learners to the next stage because I don’t want ‘to become unnecessary’ (Grow, 1991/1996, no page).

Grow suggests that the role of the Stage 4 teacher is ‘not to teach subject matter but to cultivate the student’s ability to learn’ (Grow, 1991/1996, no page). This brings to mind the old adage that secondary teachers are seen as teachers of their subject whereas primary teachers are teachers of children. This is completely unfair but secondary teachers do think differently about their jobs because they have very different pressures to their primary colleagues. Being a primary teacher and a secondary teacher are two very different things as is being an early years’ teacher in comparison to an upper primary school teacher.

Phil Race’s model of learning:

- Wanting to learn

- Learning by doing

- Learning through feedback

- Making sense of what has been learned

In reading what Knowles has to say about the way adults learn I think that this reflects what I was hinting at earlier in regard to how I learn. As an adult learner I do need to know why something is relevant; that I am able to make decisions about what I am learning; that what has come before is important but what comes next is valuable and useful in a practical way. An interesting observation is that adults are life-centred rather than subject-centred.

I need to think about how I facilitate small group teaching. I know the theory and how to it works with children but I have not really applied these strategies to working with my students this year. I need to use more co-operative learning strategies. Perhaps that is what I do need to learn on this course is how to shift from being a teacher to becoming a facilitator of my students’ learning.