In this week’s input we investigated the way in which technology can be used in teaching Music. In an increasingly digital age it is important that we give children skills which are fit for the 21st century. Becoming familiar with tools such as garageband, wavepad and Audacity gives children opportunities to develop skills for digital creative work. For example, creating and editing their own podcasts, audiobooks and radio shows. From my own education, music seemed to be considered superfluous. However, it can provide employable skills and should not be seen as extraneous to the curriculum.

In Csikszentmihalyi’s description of creativity, they refer to access to a ‘domain’ and ‘field’. The former refers to the form of the creative process and the latter refers to the place where the product of creativity can be received by others. This access to creative spaces, mentors and tools is affected by socioeconomic, cultural, and social capital (Csikszentmihalyi, 1996).

With the decrease in free instrumental instruction in Scotland (Tes, 2020), the purchasing of instruments and the financing of individual tuition, can act as a barrier to music and developing musicality. This leads to a divide between who is able to access music education. Audio-editing software, such as the examples mentioned above, are free to use and could decrease this divide. Most families have at least one device which their child can use and all schools will have a bank of devices that can be shared among the children. The use of technology in music can therefore close the divide between rich and poor and the unequal access to musical experiences and education.

This is particularly important given the benefits of music education. In their TED Talk, Anita Collins outlines the cognitive benefits of music education and argues that it should be an essential part of education. Through MRI scans, musicians brains have been shown to be structured differently to non musicians. Musicians have a larger ‘bridge’ between the two hemispheres, improved executive function and better memory systems (Collins, 2014).

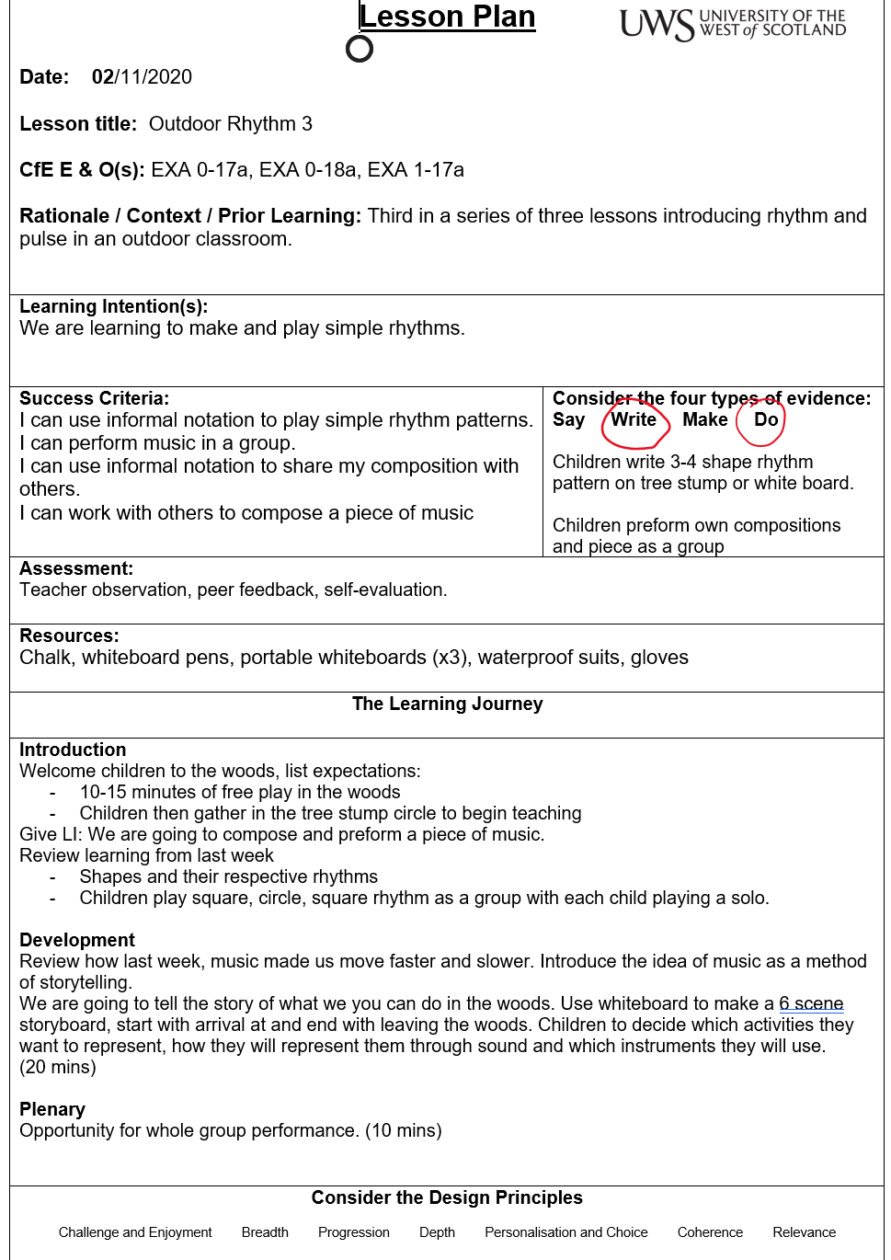

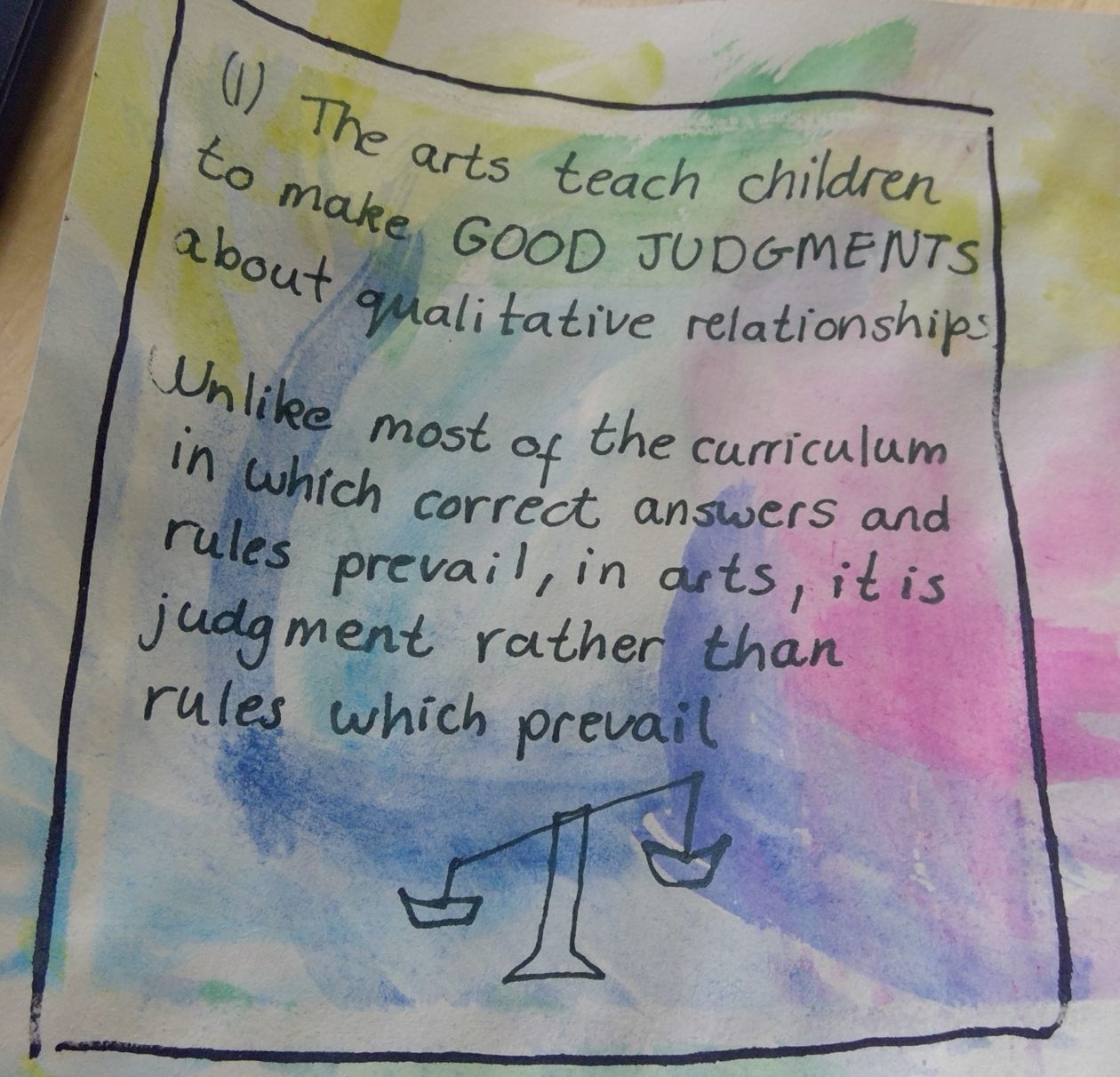

These technologies allow files to be saved without the need for recording music in either graphic or formal notation. This could free children’s creativity as they can focus on exploration of sound, rather than feeling held back by the need to write down their compositions. This emphasis of experimentation and exploration encourages children to take risks and be more confident in acting creatively.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M (1996) Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention. New York: Harper

Eisner, E. (2002) The Arts and Creation of Minds. New Haven: Yale University Press.

TED (2014) Anita Collins: The benefits of music education. October 2014. Available at: https://www.ted.com/talks/anita_collins_the_benefits_of_music_education?language=en (Accessed: 4 January 2021).

Tes (2020) Number of music pupils drops for third year in a row. Available at: https://www.tes.com/news/schools-number-music-pupils-drops-third-year-row. (Accessed 4 January 2021)