This week, we explored two excellent teaching resources that we could deploy in the classroom. In our visual arts input, we discussed emotional learning cards and Taylor’s Model of Assessment and in our music input, we explored Charanga, an online teaching resource.

Visual Arts

Often, the development of emotional wellbeing through expressive arts is achieved through analysis of artwork. However, in primary schools, lessons based upon the appreciation and analysis of art are limited (Fleming, 2012). As such, this week we used emotional learning cards and Taylor’s Model of Assessment to develop our emotional wellbeing through critical analysis of art.

Often, the development of emotional wellbeing through expressive arts is achieved through analysis of artwork. However, in primary schools, lessons based upon the appreciation and analysis of art are limited (Fleming, 2012). As such, this week we used emotional learning cards and Taylor’s Model of Assessment to develop our emotional wellbeing through critical analysis of art.

On one side of emotional learning cards, there is a piece of artwork and on the other side there are some questions surrounding the art. Firstly, we worked in pairs to discuss the  questions and ideas noted on the back. I have never critically analysed a piece of artwork before and as such, may have struggled to generate conversations surrounding this artwork had the ideas on the back of the card not been there to prompt our discussions. This highlights the lack of art analysis present throughout my education, further reinforcing points made by Fleming (2012).

questions and ideas noted on the back. I have never critically analysed a piece of artwork before and as such, may have struggled to generate conversations surrounding this artwork had the ideas on the back of the card not been there to prompt our discussions. This highlights the lack of art analysis present throughout my education, further reinforcing points made by Fleming (2012).

I believe that children would be able to provide interesting and unique insights without substantial guidance. Nevertheless, as a practitioner, it would be important to note that some children may require prompting to stimulate ideas. However, it is important that practitioners nurture pupils’ creativity rather than forcing their own ideas upon children (Bruce, 2004 cited in Craft, 2007).

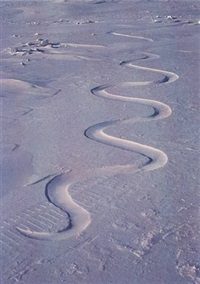

Taylor’s Model of Assessment uses questions under four headings: process, form, content and mood to critically analyse art. Process focuses on how the art is created while discussions around form involve shape, colour and cohesion. Content involves discussing messages broadcasted through the art and mood involves the feelings and emotions provoked by the art. We worked with a partner to create a video that answered one question from each of these headings based on the piece of art pictured on our emotional wellbeing cards (see below). We were able to generate answers, largely, from our own thoughts, experiences and ideas. However, one answer (our answer to the content question) was prompted by ideas on the back of our card.

As well as linking to the UWS (2018) Graduate Attribute of being emotionally intelligent, I feel this activity also benefitted us as future teachers. My partner and I linked our piece of art to immigrant families and feeling like you do not belong and we were able to link the thoughts and emotions provoked by the art to teaching practice. This illustrates that art allows us to delve deeper into both our own emotions and wider societal issues (Fleming, 2012).

Music

This week, we explored Charanga, an online educational resource for teaching music. The website provides lessons plan for all primaries. It provides 6 units for each year group that span over a 6-week block and allow children to listen to, appraise, sing and play songs (see below).

This week, we explored Charanga, an online educational resource for teaching music. The website provides lessons plan for all primaries. It provides 6 units for each year group that span over a 6-week block and allow children to listen to, appraise, sing and play songs (see below).

Charanga is an excellent educational resource. Some of the most common challenges towards expressive arts teaching: pressure to reach literacy and numeracy targets and a lack of confidence in teachers (Mills, 2008; Russell-Bowie, 2013). Charanga helps to overcome these issues. As has already been discovered throughout the module, expressive arts lessons provide ample opportunity for inter-disciplinary learning. The website highlights where lessons can be linked to other curricular areas, allowing for literacy and numeracy to be taught alongside expressive arts. Furthermore, Charanga provides very explicit outlines for each lesson which can help teachers who lack confidence in teaching music.

Before this module, I lacked confidence in teaching expressive arts subjects. My confidence has grown thanks to the skills and knowledge I have gained and the teaching resources and techniques I have accumulated each week.

Reference List

Craft, A. (2007) Creativity and Possibility in the Early Years. [Online] Available: www.tactyc.org.uk/pdfs/reflection-craft.pdf [Accessed: 5 November 2019]

Fleming, M. (2012) The Arts in Education: An introduction to aesthetics, theory and pedagogy. London: Routledge.

Mills, J. (2008) The Generalist Primary Teacher of Music: a Problem of Confidence. British Journal of Music Education. [Online] Vol.6(2), pp. 125-138. Available: Cambridge University Press. [Accessed: 5 November 2019]

Russell-Bowie, D. E. (2013) A Tale of Five Countries: Background and Confidence in Preservice Primary Teachers in Drama Education across Five Countries. Australian Journal of Teacher Education. [Online] Vol.38(7), pp. 59-74. Available: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1016005.pdf [Accessed: 5 November 2019]

Drummond, M. J. (2006) Room 13 Case Study Report. [Online] Available: room13international.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Room13-Case-Study-Report-Nesta-2006.pdf [Accessed: 5 November 2019]

of nurturing creativity and allowing children to initiate learning. It aims to give students creative autonomy and the freedom to focus their artwork on the things they like (Adams et al, 2008, Room 13 International, 2012). This concept has been adopted throughout the UK and the wider world. As of 2006, there were six Room 13’s in the UK: five in primary schools and one in a secondary school (Drummond, 2006).

of nurturing creativity and allowing children to initiate learning. It aims to give students creative autonomy and the freedom to focus their artwork on the things they like (Adams et al, 2008, Room 13 International, 2012). This concept has been adopted throughout the UK and the wider world. As of 2006, there were six Room 13’s in the UK: five in primary schools and one in a secondary school (Drummond, 2006).

named Vashti finishes an art lesson in school with a blank sheet of paper. When questioned by her teacher she says simply, “I just can’t draw.” She is then prompted by her teacher to make at least one mark on the page. Vashti obliges and stabs one dot onto the paper. She returns to class the next morning to see her dot framed on the wall. This inspires Vashti to experiment with her creation and soon she has drawn and painted dots in various sizes and colours and has entered her paintings into the school art show.

named Vashti finishes an art lesson in school with a blank sheet of paper. When questioned by her teacher she says simply, “I just can’t draw.” She is then prompted by her teacher to make at least one mark on the page. Vashti obliges and stabs one dot onto the paper. She returns to class the next morning to see her dot framed on the wall. This inspires Vashti to experiment with her creation and soon she has drawn and painted dots in various sizes and colours and has entered her paintings into the school art show.