The Power of the Practitioner.

Some implications from research in the field of neuroscience and attachment theory for current practice in the early years.

When early learning and childcare is fully open things will be different. There will be restrictions on how resources can be used and on the amount of time children spend in establishments. Readjusting to the return will have an impact on children, practitioners and parents and carers.

Something that will be the same however, is the relationships practitioners create with children, families and each other.

We know that relationships are at the heart of effective early years practice but perhaps it is more important than even to remember this.

In this short blog I will outline two examples of knowledge from the field of neuroscience and one from attachment theory, describe how these apply to practice and suggest ways we can use this knowledge to maximise opportunities to promote feelings of safety and support the conditions in which children can develop and learn effectively.

We must remember that brain development is particularly rapid in the early years and therefore we should be particularly mindful of our impact on this.

How children feel matters.

Consider the ways that children naturally like to ‘be’; thinking, making choices, supported by adults who are calm and pleasant. These are the conditions in which children will be emotionally invested in what they are doing. In such conditions with this emotional investment, the brain releases the neurotransmitter dopamine which makes us feel good. Dopamine also drives attention which in turn drives development and learning.

If we ignore children’s emotional investment and perhaps veer towards more controlling and restrictive methods these may invoke feelings of anxiety. These negative feelings can lead to the release of other neurotransmitters and hormones such as cortisol and serotonin which decrease attention and effectively block learning.

We need to consider the environment, choices available to children and our interactions and ask how can we maximise children’s feelings of wellbeing and emotional investment and therefore their opportunities to learn?

How practitioners and parents and carers feel also matters.

The same processes as described above for children also take place in adults, so it is important to consider this. We all have a responsibility to contribute to the ethos in our establishments, we are affected by and in turn affect this. How we treat each other matters, so what does this look like in practice? The environment and relationships between staff and parents will impact on this.

Interactions really matter.

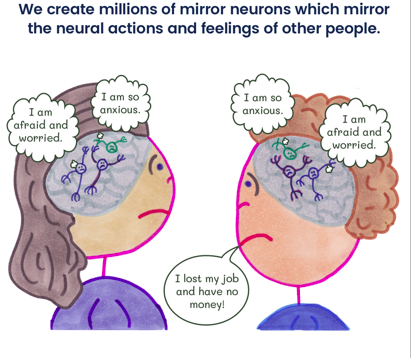

The way we interact and communicate with children has a direct effect on their brains. Mirror neurons trigger responses in children’s brains that are a direct result of our communication, verbal and non verbal. Babies are attuned to the nuanced responses of their caregiver and we need to remember that young children are too. Our facial expressions matter, do we physically go to their level when possible to communicate? What about our tone of voice and body language?

Perhaps we will be less likely to approach children and be close to them as a result of covid, and of course we must be mindful of guidance in this area but we also need to make sure that our communications and interactions with children still have the power to trigger ‘positive’ mirror neurons.

“A teacher’s moment by moment actions and interactions with children are the most powerful determinants of learning outcomes and development. Curriculum is important but what the teacher does is paramount” Copple and Bredekamp, 2009, p,xii

Relationships influence expectations.

We are all affected by the relationships we had in our early years. Young children develop ‘working models’ based on their experiences that shape their expectations of how adults will behave. Importantly, these will influence how children respond to adults no matter how the adult behaves. For example, two children with different experiences and views of how adults behave will respond differently to the same interactions as a result of their expectations.

Children’s responses will perhaps be more influenced by their ‘working models’ and perceptions of adult behaviours after lockdown. Children who have had positive experiences and interactions that have supported them to have a positive self-view will expect the adults in early years settings and schools to behave in these ways towards them and they will respond to the adults accordingly. Children who have had less positive experiences will not expect things to be positive and may pre-empt adult interactions with ‘negative’ responses. Children’s views of adults and their own histories can therefore have a powerful influence on how they view themselves.

The good news is that all of us who work with children have the power to influence their ‘working models’. For children who have negative expectations it takes more effort on the part of the adults to change their perceptions. They will need more positive experiences to begin to change their (unconscious) views of how adults will behave. Sometimes the children who are described as being ‘harder to engage’ and ‘confrontational’ are the very children we need to work harder with to begin to influence their views of adults. When you come across these children don’t give up. It may take time and effort but with persistence, positive interactions and by communicating a belief in children you have the power to make a difference.

Reference taken from. Copple, C., & Bredekamp, S. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice in early childhood programs serving children from birth through age 8. 3rd ed. Washington, D.C.: National Association for the Education of Young Children.